The Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) is currently hosting the last stop of the major retrospective exhibition “The World of Charles and Ray Eames.” The show, which is also documented in a lavish companion catalogue of the same name, debuted at the Barbican in 2015 and has been touring internationally since then. Due to the voluminous and diverse nature of the couple’s multimedia output, the Eameses present an inherent challenge in terms not only of basic classification but also of curation, exhibition, and display, activities that they themselves pursued in many projects. Should they be considered as designers, architects, or filmmakers? Philosophers, even? As the exhibition does, it is best to just present and regard the work in all of its complexity while considering the Eamses’ own self-definition of being “tradesmen.”

Accordingly, it is appropriate to begin with the same caveat that Catherine Ince uses to begin “Something About the World of Charles and Ray Eames,” the introductory essay to the exhibition catalogue: “The rich and complex history of Charles and Ray Eames, their lives, their Office and its prolific output is almost impossible to summarize. This publication, like the exhibition it accompanies, does not attempt to provide a definitive account of the Eamses’ history, but foregrounds work and ideas that continue to resonate today.”

The Eameses

Charles Eames was born on 17 June 1907 in St. Louis, Missouri. He attended Washington University there for a while but never graduated (according to legend, he was expelled for supporting the work of Frank Lloyd Wright). Charles then started working in an architectural office and although he was never licensed, he opened his own office in 1930, designed several buildings, and by 1940 had been invited by Eliel Saarinen to the Department of Industrial Design at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. During his time there, he also worked part-time for the [Eliel] Saarinen & [Eero] Saarinen firm and made his first film, a documentary that featured the Academy’s Instructor of Ceramics and Pottery, the Finnish-born Maija Grotell. Charles eventually collaborated with Eero Saarinen on designing a furniture set that importantly included a molded plywood chair and won the New York Museum of Modern Art’s Organic Design in Home Furnishing competition in 1941. Despite their victory, the chair could not be mass-produced easily or cheaply, especially after the defense efforts of World War II restricted the availability of materials.

Ray Kaiser was born in Sacramento, California on 15 December 1912. She initially studied painting with Hans Hoffman and was a member of the American Abstract Artists Group in New York before transferring to the Cranbrook Academy. There, she met Charles and contributed the drawings that were submitted for his and Eero’s Organic Furniture project. Even though Charles was already married with a child, he got a divorce and married Ray in 1941, and the new couple moved to Southern California. Once there, Charles took a job working in the art department of MGM Studios for a while, and this cinematic experience would prove to be very important to their later work. It should go without saying that this unusually volatile combination of an abstract artist and a mathematical architect, both of whom were also highly driven and curious about the world, would inevitably lead to an incredible, even overwhelming, body of work.

Despite their earlier failure at creating mass produced furniture, Charles and Eero remained lifelong friends and continued to collaborate on other projects, such as the Case Study Houses # 8 and # 9 for Arts & Architecture magazine’s Housing Program in 1945. Ray also designed several covers for the magazine. Charles and Ray ended up redesigning and building House # 8 in 1949 to fit unobtrusively on a hilly meadow in Pacific Palisades, California, while House # 9 was built nearby for a friend. Eero passed away in 1961, but his firm Saarinen and Associates was still finishing the Dulles Airport in Washington D.C. At the same time, C.F. Murphy Associates were constructing Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, and both firms needed a new kind of public seating for their respective projects. In response, the Eames Office created the Tandem Sling Seating in 1962, and the model is still in production and used in many airports today.

After moving to California, Charles and Ray continued to experiment on perfecting the design for a good quality, mass produced chair of molded plywood. The process first led them to create improved splints and other medical supplies for soldiers injured in World War II, and they then applied the same methods to the chairs. Though the completed chair was first manufactured by Evans Products, Charles was awarded a one-man show at the MOMA in 1946 after which the Herman Miller Furniture Company took over production and turned the chairs and the Eameses into a national success story. Considering the timing, much of the couple’s success has been linked to the post-war rise of the middle class throughout the country’s newly developing suburbs. Their influence was so popular that it served as the inspiration for William Holden’s character McDonald Walling in Executive Suite (1954), a movie for which Charles provided designs and samples of shop-talk dialogue. Charles was also a lifelong friend of director Billy Wilder and assisted with the sets and certain footage on The Spirit of St. Louis (1957) and other movies, and these cinematic experiences were documented in the three-panel slide show Movie Sets (1971). Ray also designed the opening credits for Love in the Afternoon (1957).

The Eameses appeared on an episode of Home with Arlene Francis in 1957 to preview the Eames Lounge Chair, one of their most famous products, before it was commercially released. Francis refers to “Charles Eames” as a “household word.” Nevertheless, the appearance has been noted as an uncomfortable example of the era’s sexual politics, as Charles apparently confuses the host by making numerous concessions to Ray’s contributions and referring to all of their activities in the first person plural (i.e., “we”). Ultimately, despite inviting Ray on stage and trying to accommodate the egalitarian situation as graciously as possible, Francis still feels obligated to conclude with the strained comment that Ray remains “behind the man but terribly important”, and she is left behind as Charles alone introduces the chairs on display. The sequence ends with a clever short film that shows how the Lounge Chair and its footstool are assembled and used before being partially disassembled and packaged for shipment. Another example of the respect and prominence that the couple had achieved can be seen in the India Report (1958), which was commissioned by the government of that country and led to the establishment of its National Institute of Design.

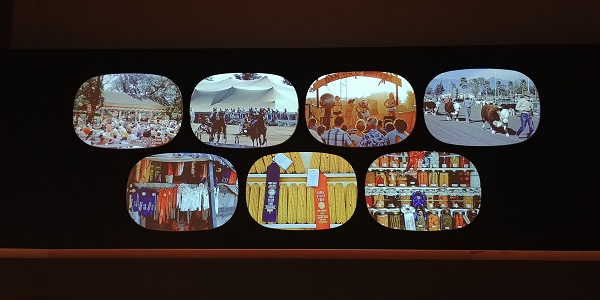

An early example of the Eamses’ extensive filmmaking and exhibition planning, A Rough Sketch for a Sample Lesson for a Hypothetical Course (1953), which was prepared with George Nelson and Alexander Girard for the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Georgia, has been considered one of the first public multimedia presentations ever delivered in America. Years later, for the pavilion of the American National Exhibition in Moscow, the Eamses created Glimpses of the USA (1959), a presentation that used over two thousand still and moving images projected on seven screens in twelve minutes to portray the vastness inherently involved in the daily life of a large country populated by millions of people.

Over the years, the Eameses produced over one hundred films, often for corporate clients such as Polaroid, Westinghouse, and different branches of the US Government in order to explain their technical and scientific work and products to the general public. Accordingly, it should be noted that some scholars, such as Sam Jacob in the exhibition catalog essay “Context as Destiny: The Eamses from Californian Dreams to the Californication of Everywhere”, have problematized such affiliations in contrast to the couple’s otherwise liberal embrace of hospitality, domesticity, nature, and human life in all of its aspects. Regardless of the sponsors, the couple’s interactive and educational exhibition Mathematica: A World of Numbers … And Beyond (1961) remains on permanent display at the Boston Museum of Science, the New York Hall of Science, and the Henry Ford Museum. The Eamses also collaborated again with Saarinen and Associates to create Think, a presentation for the IBM Ovoid Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. The installation, which was initially sketched in two IBM Fair Presentation films from 1962 and 1963, respectively, used massive hydraulic lifts to move the audience and the live presenter from the ground into and around a large theater featuring twenty-two screens and showing another overabundance of film and images in order to explain the concept of a computer. The production was also documented in the short films IBM at the Fair (1965) and View from the People Wall (1965).

In 1975, the Eameses debuted their most ambitious project and complex endeavor, the massive exhibition The World of Franklin and Jefferson which toured internationally before opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to commemorate America’s centennial. Featuring an overwhelming array of texts, images, and objects, including most famously a stuffed bison, the display has been described as an early analog attempt to create a digital hypertext experience, and it was therefore criticized at times for being bewildering in terms of the volume of objects and the amount of text involved, most scathingly after it opened at its final destination back home. The large undertaking resulted in the production of the original The Franklin and Jefferson Proposal Film (1973) along with two other movies, Paris: The Opening of an Exhibition (1976) and The World of Franklin and Jefferson (1977), and a companion book of the same title (all three documentaries are available on The Films of Charles & Ray Eames, Vol. 3: The World of Franklin & Jefferson).

Despite some of the disappointment caused by the negative reactions to the exhibition, the Eameses still created what has arguably become their most famous film, the nine-minute-long second version of a cleverly illustrative depiction of the mathematical concept of the Powers of Ten (1977; the first version from 1968 is officially known as A Rough Sketch for a Proposed Film Dealing with the Powers of Ten and the Relative Size of Things in the Universe). The film begins with a one-square-meter image of a picnicking couple from which the camera slowly zooms out at the steady rate of an exponential increase, first to ten square meters, then one hundred, and so on until it soon reaches deep into outer space. After this, the camera zooms back quickly to the original scene and then astonishingly continues to go through the man’s skin, cells, and DNA into the smallest known limits of the subatomic world.

All of these projects and countless more were produced with the assistance of the large staff that worked at the warehouse the couple had opened in 1943 at 901 Washington Boulevard in Venice Beach. Like their unique home, the Eames Office became another unusually lively and iconic location that was closely associated with the pair. Well ahead of its time, it featured a uniquely modular design that used moveable walls and other innovative features to isolate different areas and allow them to be quickly and easily modified and adapted for different purposes; for example, a room could be used one day as a film or photography set and then be completely dismantled the next to allow for a space where drafting tables could be set up.

Charles Eames passed away on 21 August 1978. Ray kept the studio going until passing away on 21 August 1988 (one eyewitness believes that she purposefully hung on in the hospital until reaching this date, the ten-year anniversary of Charles’ death). The studio was closed shortly thereafter and its contents shipped to the Library of Congress, where they remain today. Though a detailed finding aid has been prepared, the more than one millions items have proved to be so voluminous that they still have not been completely processed and documented. Another selection of industrial design prototypes and related production items are now housed at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany, and the company remains the long-time European manufacturer of Eames furniture.

Fortunately, the fascinating process of dismantling and packing up the dizzying array of items from the studio was captured by the couple’s grandson, Eames Demetrios in the short documentary 901: After 45 Years of Working (1990). Furthermore, as reflected by its thorough and comprehensive website, Demetrios and other family members have continued to keep the Eames Office functioning as a business and have helped preserve their grandparents’ legacy in several books and films. They also run the Eames Foundation and maintain the Eames House, which is available for external tours only by appointment.

The Exhibition

The World of Charles and Ray Eames exhibition strikes a good balance by introducing all aspects of the Eameses’ most important work in a generally chronological order without becoming overwhelming. The initial rooms feature Ray’s paintings and magazine covers and the pair’s early splints and plywood and fiberglass chair prototypes. Primarily, there understandably are quite a number of different Eames chairs and other furniture on display throughout, but these are augmented by a miscellany of archival photographs, letters, pamphlets, and other objects either designed, created, or collected by the couple.

The other major component of the exhibition consists of the numerous Eames films that are displayed in different ways. Some are projected against the walls either with or without sound, and in this way Buddy Collette’s jazzy soundtrack for the short documentary The Fiberglass Chairs: Something of How They Get the Way They Are (1970) provides an appropriately modernistic twentieth-century soundscape that can be heard throughout most of the initial exhibition area, while a noisier, seven-screen recreation of Think in a side projection room provides much of the soundtrack for a later part of the exhibition. One wall features a reconstruction of Glimpses of the USA, which can be listened to with headphones while sitting in one of the extremely comfortable lounge chairs, complete with ottomans. All of the chairs that are set up to view the films or work at the interactive stations consist, naturally, of a selection of different kinds of very comfortable Eames designs. Other films projected against the walls in large format include House: After Five Years of Living (1955), Solar Do-Nothing Machine (1957), Kaleidoscope Shop (1959), Tops (1969), and both versions of Powers of Ten, along with the three-screen slideshow Tanks (1970), which the office created as part of their commission to design a National Aquarium, a project that was ultimately abandoned. Smaller screens with headphones scattered throughout offer other films, such as the product presentations for the S-73 (1954) compact sofa and the Polaroid SX-70 (1972) camera.

OMCA staff members occasionally drop marbles down the Musical Tower (c. 1950s). As they fall down the tall, thin structure, they strike either dismantled metallic xylophone keys or wooden blocks in order to play a melody composed by Elmer Bernstein (who also did most of the Eamses’ film soundtracks) with percussive accompaniment. Sometimes, a marble gets stuck in between the slats but is dislodged by a following one, and then the two together roll down playing the instrument in even more unique, doubled patterns.

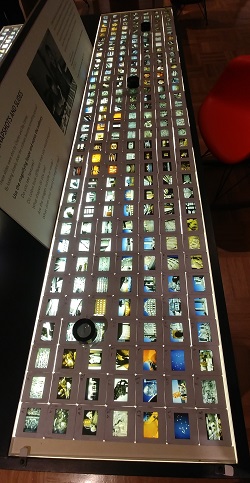

Interactive work stations allow visitors to directly experience some of the materials. They can fold organically-shaped pieces of two-dimensional paper to make three-dimensional structures and project the resulting shadows against a wall. Other stations allow visitors to play with and construct structures using both the giant and the small versions of the House of Cards (1952), or they can look through a variety of different kinds of kaleidoscopes or at an array of slides with a magnifier. One table features books about Eamses’ most important friends and influences, including Saarinen, Alvar Aalto, Buckminster Fuller, and Billy Wilder. It should also be noted that there is another Eames connection in the fact that the OMCA building, which was opened in 1969, was designed by Kevin Roche, a principal design associate at Eero Saarinen and Associates who ultimately completed a number of Saarinen’s projects posthumously through his own firm, Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates.

Having contributed so much to the material culture of the modern world, it feels poignant to end with a well-known Eames quote that presciently recognized the problems created by such overabundance and which now need to be solved: “The scary fact is that many of our dreams have come true. We wanted a more efficient technology and we got pesticides in the soil. We wanted cars and television sets and appliances and each of us thought he was the only one wanting that. Our dreams have come true at the expense of our lakes and rivers. That doesn’t mean that the dreams were all wrong. It does mean that there was an error somewhere in the wish, and now we have to fix it.”

Text and photos: Nikolai Sadik-Ogli

Bibliography

Albrecht, Donald. The Work of Eames: A Legacy of Invention. New York: H.N. Abrams, 2005.

Demetrios, Eames. An Eames Primer. New York: Universe Publishing, 2013.

Drexler, Arthur. Charles Eames: Furniture from the Design Collection, the Museum of Modern Art, New York. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1973. Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1712

Eames, Charles and Ray. An Eames Anthology: Articles, Film Scripts, Interviews, Letters, Notes, Speeches. Daniel Ostroff, ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

_____. Essential Eames: Words and Pictures. Eames Demetrios and Carla Hartman, eds. Weil am Rhein: Vitra Design Museum, 2017.

The Eames Family. Eames: Beautiful Details. Gloria Fowler and Steve Crist, eds. Los Angeles: AMMO Books, 2012.

Eidelberg, Martin. The Eames Lounge Chair: An Icon of Modern Design. Grand Rapids: Grand Rapids Art Museum, in association with Merrell, 2006.

Ince, Catherine and Lotte Johnson, eds. The World of Charles and Ray Eames. New York: Rizzoli, 2015.

Kirkham, Pat. Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995.

Koenig, Gloria. Charles & Ray Eames, 1907-1978, 1912-1988: Pioneers of Mid-century Modernism. Cologne: Taschen, 2005.

Kries, Mateo and Jolanthe Kugler, eds. Eames Furniture Sourcebook. Weil am Rhein: Vitra Design Museum, 2017.

Margaret H. McAleer, et al. Charles Eames and Ray Eames Papers: A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress. Washington, D.C.: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, 2016. Retrieved from http://findingaids.loc.gov/exist_collections/service/mss/eadxmlmss/eadpdfmss/1998/ms998024.pdf

Neuhart, John and Marilyn, Ray Eames. Eames Design: The Work of the Office of Charles and Ray Eames. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1989.

Neuhart, Marilyn. The Story of Eames Furniture. Berlin: Gestalten, 2010.

Schuldenfrei, Eric. The Films of Charles and Ray Eames: A Universal Sense of Expectation. Abingdon: Routledge, 2015.

Filmography

901: After 45 Years of Working (1990) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oe60mCCDP2E)

Eames: The Architect and Painter (2011) (trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_YMzmuBBBzo)

Executive Suite (1954) (trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJ_kIvPp53Q)

The Films of Charles and Ray Eames, Volumes 1-6 (2000-2005). Selected films and excerpts available on-line:

The Fiberglass Chairs: Something of How They Get the Way They Are (1970) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PYptIkjS6zk)

Glimpses of the USA (1959) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ob0aSyDUK4A)

IBM at the Fair (1964) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2UZYG33D2B4)

Powers of Ten (1977) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fKBhvDjuy0)

Solar Do-Nothing Machine (1957) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kv6YvKPXQzk)

SX-70 (1972) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lo_1pyQ7xvc and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXPYera597U)

Tops (1969) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UJ-VFMymEiE)

View from the People Wall (1965) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M6BA4baRcVo)

Home with Arlene Francis (1957) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IBLMoMhlAfM)

The Spirit of St. Louis (1957) (trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pADw8x4zjsk)

Websites

Eames Music Tower: http://blog.barbican.org.uk/2015/12/curator-picks-musical-tower/

Eames Office: http://www.eamesoffice.com/

Eames Office YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/EamesOffice/videos

Exhibition at OMCA: http://museumca.org/exhibit/world-charles-and-ray-eames

Herman Miller Furniture Company: https://www.hermanmiller.com/

Vitra: https://www.vitra.com/en-us/corporation/designer/details/charles-ray-eames