When I first entered the exhibition Dance! Movement in the Visual Arts 1880–2020 at HAM, the Helsinki Art Museum, I had great anticipation to experience a corporeal and active gallery space. Instead, I experienced a static space that disturbed my senses. There were drawings, photographs and sculptures of immense kinetic movement, expressive gestures and the momentum of energetic lines. There were giant video projections of rhythmic motion that played with dissonance of pace. Yet in disheartening contrast, I observed the rigid movements of the viewers as they mostly glazed over each piece, scanning with only their eyes. These viewing bodies were inactivated and trapped in habitual postures.

I began to question my own viewing habits and observe those happening around me. I began to imagine how I might view artwork with authentic interaction and free myself from social norms of appropriate and expected museum behavior. After reflecting on my initial experience of the exhibition, I decided to return two more times to conduct a series of experiments and make observations. My visits led me to ask – how do we dismantle conventional viewing as a static mode reliant on the heroized sense of sight and engage artworks with our entire body?

Viewing art is not a transactional moment of perception between only two isolated entities – the artwork and the viewer. Rather, perception is phenomenological and happens between every material, body and space, however nondescript. The gallery space is a matrix of relationships; there is a narrative continuum of the artists’ manifest ideas, the curators’ vision and arrangement of artworks, and every space between – floor, walls, windows, air and viewer’s bodies.

I began to suspect that what I propose as “art” lies in these spaces between as an event in time. In response to the exhibition’s theme of dance, I conceive of this event as a dialogical dance in that it is a fluid exchange of energy produced from the symbiotic relationship of image, medium, body and spirit. My experiments actively asked: How might viewing in embodied ways allow us to enter into the dialogical dance of listening and responding to experience art that “happens”?

I

During my first visit to the exhibition I noticed that while sitting to view the video piece by Sini Pelkki₁ I kept wondering about its duration. After reading the label to learn it was 16 mins, I returned to the bench to watch, but kept trying to assess how much time had passed. I later realized that I was approaching viewing as a transactional affair where I would have permission to take leave when I had taken in all that was being offered me. I also became aware of this sense of an exclusive ownership of the artwork – that I was receiving something second hand with a particular life-span. This produced a sense of exclusion that made me want to disengage.

In contrast, when I discovered another video piece, Kotka₂, reflected onto the surface of a kinetic light sculpture₃ along a long wall, I was drawn into a space that felt deep and intimate. I felt an inner-related relationship in the space between myself and the images of overlapping artworks. I began to walk along the wall, animating this reflection space with my body’s movements. I let my eyes and joints become freed to move intuitively in response to the moving shapes. I was creating my own abstracted compositions in the frame of my sight, limited only by the position of my head at any given moment. My active dialogue with these merging of images was producing art that was an event in real time (not the display of video recall). This art as an event cannot be captured, because even though my phone camera could video this reflection combination, viewing that video then renders it in the same sphere that I experienced the isolated video – static and unrelated to my body. The art that was transpiring only existed in the space between me and the wall where I was experiencing the event of the reflection through my perceiving and moving my body in real time. It also differs because the dialogue of my active viewing was initiated from an internal drive of curiosity, not an external pressure to consume for a class assignment. Habitual modes of viewing can be more like social performances of roles, but this momentary break was an authentic, resonant experience.

However, the resonance of my dialogue with the artworks was not sustainable. The very immensity of this deep space deterred me from lingering because I feared it was taking too much time away from my other obligations. I experienced time as an external pressure. Anxiety is produced from living in a society of acceleration, driven, in my case, by a fear of missing out on future potential engagements and getting behind on other tasks in my day.

Hartmut Rosa’s theory of acceleration (as contrasted by resonance) proposes that our society functions on a model of dynamic stabilization where in order to sustain the status quo, we must continue to grow and expand. We operate in service to our survival instincts as they’ve been encoded by capitalism which demands continual productivity. The energy that fuels us comes from a need to keep up, to secure our place in the world, to not fall behind. Rosa recognizes how we are propelled by a constant need to take hold of all that is attainable and accessible. It was this tension between a fear of missing intaking the entirety of the video piece and needing to sustain the momentum of my day within the limited resource of time that produced my anxiety and inability to linger with the artwork.

When two goals are equally persistent and pulling in opposite directions, the experience is nullified and the very unproductivity or non-happening that we fear occurs. The constant tension in our subconscious of this ineffective expenditure of our attention and time (especially when the economy we live in capitalizes on these limited, material resources) leads to us capitulating and we step away from the artwork.

II

Instead of resigning to this tension and my disappointment in the exhibition, I decide to show up differently. I have a suspicion that there may be more resonance latent within this artwork than my first customary glaze-over was revealing. Perhaps I need to do something for the artwork, to address it and invite the dialogue of dance the curators imagined. I begin to ask myself a question based on one of the curator’s definitions of art as “something that happens to me.” How do I actively show up for this happening? How do I engage in the resonant dialogue of art transpiring in real time? To begin with, how do I sit on the bench or in what manner do I stand? Where and how do I direct my gaze?

It seems that in our striving to improve our world, we have forgotten that it is our own humanity that is our greatest work of art and that everything flows first from our internal world. What if, instead of saying that an artwork is failing to enrapture and communicate, we re-grounded the responsibility in ourselves?

When we encounter an artwork, our default mode is to perceive it as an image. Our eye is paramount, processing it photographically and rendering it flat. Viewing becomes more like scanning over a surface. How might we stop and consider our own neglect of attention? If we lingered long enough might we cultivate a relationship with the artwork and begin the dance of dialogue? So often viewing art is a passive consumption where we are being served another’s idea, talent or mastery of skill, but a dance is when every element (blank spaces of wall, the ceiling, fire-hydrants, air and so on) is raised to the same level of importance (worthy of our attention) as the artworks and viewing becomes a cohesive, relational event.

I began my experiments by returning to the exhibition to first simply practice lingering. I observed how others were interacting with and viewing the artwork. I made the intention to not look at my phone to see how much time had passed. I watched the same video piece 5 times over. I stood in odd places for comparatively inordinate amounts of time. I resolved to not seek a result or something to gain, but to offer my presence.

From these experiences, it became evident that the core problem was my conception of time. The scarcity of time when reduced to the realm of materiality demands acceleration to sustain life. Time must be re-grounded in the authentic self as a constant. What we seek in our interactions has to be internally, not externally tethered. As Byung-Chul Han suggests:

“The ‘constancy of the self’, this essence of authentic historicity, is duration, which does not pass. It does not elapse. The one exists authentically has time always, so to speak. He or she always has time because time is self, and does not lose time because of not losing him- or herself…”

When we start from the ground of the self, we enter the deep time of the soul which is eternal. When we are internally tethered, everything outside of us can be restored to a narrative continuum because we are no longer chasing physical life like fragmented ice floats in a sea of threatening abyss. When viewing artwork, this requires not just addressing the artwork as a point-based materiality in chronological time (each piece as an isolated object to consume as a point of ground to reach), but looking at the spaces between the artworks.

I practiced this when I came upon four drawings in white frames₄. They were hung so closely that only a small square section of wall remained between all their corners in the middle. I became fascinated with the mandala of shadows – intersecting triangles of varying and layered tonal value. I lowered my head to its level and fixed my eyes, holding my gaze until my vision began to blur.

When we have a point-based conception of time we make achievements and arrival spaces (finished, contained artworks) the only ground of existence and everything in-between is a non-entity, an empty void. As Byung-Chul Han writes:

“These intervals in which nothing happens cause boredom [Langeweile]. Or they appear threatening, because where nothing happens and where intentionality can find no object, there is death. Thus, point-time produces the compulsion to remove, or to shorten, the empty intervals. Attempts are made to let the sensations follow each other in quicker succession, in order to keep the empty intervals from lasting long [lange weilen]… Due to the lack of narrative tension, atomized time cannot hold our attention for long… Point-time does not permit any contemplative lingering.”

In the case of my initial encounter with the 16 min video piece₁, because I was sitting on the bench and viewing it as something isolated to consume, I perceived any moment in the video, such as when the camera moved away from the subject (the dancer’s body) or when something moved slowly or offered minimal stimulation, to be lacking and my modus operandi was to turn away. My attention was disrupted by what was coded in my brain’s perception as dead space and therefore threatening to my survival in a cultural structure of acceleration.

During this second visit of practicing lingering, I observed my own behavior at a distance by watching at what point in this video piece other viewers tended to get up and walk away. It was most often when the camera turned towards the wall or floor which seemed to be coded for them as non-information and therefore empty intervals to be shortened. They were propelled to move to seek the next thing to produce sensation.

I also noticed how the way people move and walk in museums is different. It’s its own sort of dance step: the lean forward to read the label, the self-conscious step to the side to make space for another viewer, the step back to take in the whole piece and then the passive downward swing of the body to turn as if to retreat the gaze from the artwork discreetly with a slight tone of shame or passive disinterest. There are no sidewalks or crosswalks and so people negotiate the space in uncertain diagonal pathways. There is a self-consciousness because, unlike a social marketplace, there is the additional element of the gaze that is meant to be directed only at the artwork. There is this constant cross-fire of intersecting invisible pathways of sight and it appears everyone feels restrained to the social decorum of fixing their gaze only on the artworks as that is what they’re there to see. The other bodies seem to be peripheral obstacles in the experience of the art.

I began to ask – how do other viewers become integrated into my experience of engaging the artwork? I wanted to recognize other viewers as other “artworks” that I cannot pretend aren’t there, as they affect how I perceive and interact with the artwork. I noticed there wasn’t only disregard of other bodies, but of everything else at play. The white wall in between the artworks doesn’t end neatly but leads up into a high ceiling and peculiar architecture. There is an oddly slanted ramp leading onto a platform in the first room and then there are little turns of wall, corners, a fire hydrant (etc.). I noticed how none of these elements are separate. It suddenly seemed absurd to try and absorb and comprehend separate objects. The very invitation of a curated space is to consider the intersectionality of all the elements and bodies in dialogue. The gallery is indeed a narrative continuum.

III

During my third and final visit I decided to abandon self-consciousness and social expectation and respond to the artwork, the spaces between, the other viewers, and the rooms themselves as I felt authentically compelled. I considered how I might use my entire body as a tool for seeing and absorbing. I wanted to have an experience of what I was seeing that was more related to the bodies in motion I was witnessing in the dance-themed artwork. I surrendered my phone to my friend and had her pretend to be the spectator consumed with the anxious need to capture everything. Her documentation then became the viewpoint of a fellow art-viewer: a self-conscious, sideways glimpse of my interactions (these photos are the ones used in this essay).

Armed with these considerations, I began by ascending the long staircase to the exhibition by stepping up it backwards. This was perhaps an intuitive way of priming myself for entering the space ready to challenge the conventional modes of viewing. With my head tilted back I had a spectacular view and sense of rhythm in response to the shapes of cut-out dancers and their shadows dangling from the ceiling in the staircase corridor. When I arrived at the exhibition statement, I stood with my side facing it, as if to walk away and not read it, but then turned my head to fix my eyes on the text. I felt that the people coming up behind me were uncertain about my position and avoided standing next to me. With orientation of my body in opposition to the pathway of my gaze, I became more aware of my body and all my senses as capable of participating in my experience of perceiving.

When I felt compelled to move away, my body was magnetically drawn to, as if getting caught, on the small angle of wall coming out between the first wall and the corner. It felt good to let my shoulder fall and be held in this crevice as if I was being installed along with the artworks in a natural way.

Next, I came upon the Degas sculpture of the dancer₅ and I decided to join her in her stance. As soon as I felt her body in my own mirrored posture she came to life. I became curious where her gaze was being drawn up to, so I followed her gaze. My eyes landed on the ceiling where I feasted on all sorts of interesting architectural details. While I was doing this, I felt the critical gaze of another viewer. I had to make the deliberate choice that the sculpture’s gaze and mine in response were more weighted than the gaze of this person while at the same time including their presence in my experience.

Immersed in this authentic response, at one point in the exhibition I found it wasn’t the giant video projection₁ that drew me like a bug to light, but the corner of the gallery space – a large blank space with very little light. I turned and leaned into the corner. This turned out to be an excellent vantage point – a nearly panoramic view to scan the full scene of the gallery space. I noticed how the video was this giant wooden panel leaned against the wall, forming a triangular space between it and the wall. I wondered what the angle of this lean felt like, so I assumed it upon my body by holding my arms rigidly to my sides and tilting my weight against the wall.

While leaning, I gazed at this lovely void space between the panel and the wall. The fire hydrant beyond was perfectly framed by it. This was one of my favorite spaces because it felt secret and intimate. A woman walked past the video panel while I was doing this and I was tempted to turn and succumb to the compulsory need to address her questioning gaze. I could feel her eyes flit between me and the projection panel and for a moment perhaps I felt what it’s like to be an art object regarded with this passive curiosity. Though self-conscious, I also felt freed from this woman’s position of distance as I was suddenly transformed from a consumer, into an integrated participant in the matrix of relationships in this gallery ecosystem. The isolated points of artworks (set apart and framed for my consumption) were dismantled when I realized these material elements are mere signposts to guide us in the conventions of digesting through sight. In reality, every atom flows into the next and there can be no separation. The demands of the artwork to be interpreted or understood correctly were subsumed into the whole of the environment and I became an inseparable part of its narrative continuum. Here, meaning became collective and collaborative as it could be lived through my body and created with the artwork in real time.

It is in our ability to see these empty intervals as active spaces of resonance that transforms our conception of time and space from point-based to a narrative continuum. Artwork as an object becomes a singular dot, something to achieve. The eye and brain, as isolated functions become the processors for the programmed goal – to capture and to take possession of to expand ourselves. In modern culture, with the phone as an appendix of our body, we often fulfill this goal by taking a picture. Little effort is required in taking a photo to capture and store our subject for later access. We can easily reference this image file after our encounter with the artwork – it promises instant retrieval. This is a crucial asset in a world that moves too rapidly for our natural human pace. It allows us to keep up. Yet the digital photograph, that remains detached from our bodies, contained within a phone rather than the living medium of our body, is dead.

Art as image is transmitted through a physical medium. This medium becomes the body for the image which then interacts with the perceiving body of the viewer to form mental images. Hans Belting says in his essay “Image, Medium, Body: A New Approach to Iconography”, “images do not exist by themselves, but they happen.” Images in art are an event in time, not an isolated materiality. Images continue to play out in our memory, being transformed by our imagination. Viewing something unmediated by the camera, captures what we encounter through the body’s memory which occurs, as Hans Belting says, by “first disembodying [the images] from their original media and then reembodying them in our brain.” Our ability to remember unreliant on the image file on our phone camera, happens through a process of transfer from the physical medium of the artwork to the living medium of our body. The archive of images gathered in our mind isn’t static, but is an active process of forming and transforming images with our imagination. The camera has storage and recall, but it is only memory that has personal sensitivity and depth.

When we engage with art with our whole embodied presence, the eyes and brain are demoted and all the senses are activated and function as a singular receptor. This produces a greater sensitivity and potential for intake. This receptivity cultivates vivid images to be stored in our bodies. The anxiety from acceleration in our culture of rapidity, stress and externality, is quieted as we reground time in the internal. It is the soul where images quietly gather and live on in our memory. What we take away from the event of the art encounter isn’t a purely momentary experience, but an activation of our imagination. The image as personal memory is carried on in the living medium of our bodies. It continues to work on us as we continue to transform it in our minds.

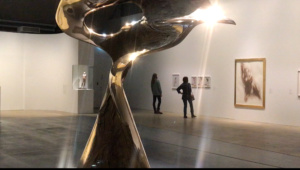

This embodied memory happened when I interacted with a large metal sculpture₆ at one end of the platform. I remember decidedly disliking it when I visited the first two times, but this time I was seeing it with my body and it felt like some archangel billowing its wings, beckoning me to nestle and rest in its shadow. So I hunkered into a ball on the floor where I felt aligned with its form. The weight and presence of the sculpture provided a nook of shelter for my body. Even without touching, I could feel its caress. On the other side of it, I discovered a circle of light and curled up into a ball to soak it in, this time transfixed not by the weight of its material presence, but the ephemerality of light and shadow that it created. In the aftermath of this experience, I can still vividly see and feel the qualities of this interaction. There is a lingering internal energy from this piece actively harbored in my body.

I began to understand that this interaction of mental and physical images is critical to the potentiality in viewing artwork. I have the power to create embodied memories instead of taking placeholder photos with the thought that I will look at them more closely later (but of course never do). Usually I am assuaged, anxiety quieted, by knowing the information or image is saved and in my possession on my phone. To counter this strong urge to capture and share my viewpoints, I decided to go through the exhibition without any phone or camera.

When I returned to the dance video Kotka₂ transposed on the long wall of the kinetic light sculpture₃, I experimented with moving along it. I played with using my eyes as I would think of operating a camera, actively questioning my viewing distance. I played with “zooming” in and out with my whole body. I bent my knees and changed viewing levels up and down. My movements created my own curation of this merged reflection space – the slow-moving light shapes and the quick abrupt movements of the dancer in the video. Unlike using a camera, I wasn’t moving to try and find the optimal perspective for capturing a composition; instead every moment and angle of perception was a living image and my entire body a receptor for gathering.

We address our world so statically, our rigid viewing posture is like the still of a photograph. But reality is more like a phantasmagoria – a sequence of constantly shifting images – with the fluid softness of a painting. We are part of this constant movement. Even when everything appears still, everything is moving on a molecular level. When we become aware of the underlying hum of constant vibration, we begin to move through space differently. We begin to let our eyes be free to drift and our joints loosen. Perhaps one reason why we have lost this ability is because we are trained in school to focus – to put on blinders and glue our eyes to a textbook or listen attentively to a teacher. Everything that adult life demands of us requires a narrowing of our senses to drown out all else in order to hyper-attune to one thing. This of course is a useful skill, but it is to the detriment of our curiosity and ability to move with the world instead of always trying to subdue or distill it. My interaction with the reflection space allowed me to reactivate this sense of all-encompassing fluid motion.

The notion of dance that framed the exhibition became for me this participation in the phantasmagoria, the shifting weight of all bodies in motion to address each other in constant, fluid dialogue. There is a transfer happening in the dance of dialogue where it is unclear who addressed who first. Fluid listening and responding happens from both ends simultaneously. As Rosa says, “who can tell the dancer from the dance?”

One such moment of dialogical dance was when I was met by a hanging tapestry piece₇, another artwork I had decidedly glazed over the first two visits. Now, I noticed that it was dancing; ever so slightly, gently blowing. Its graceful swaying was unpredictable and irregular making it more of a believable dance as the source of its movement was unclear. It became a body for my body to dialogue with and so I began to sway with it. There was something very hypnotic and peaceful about this experience as I disregarded my internal gauge of an “appropriate” amount of time to engage in this way. My swaying and that of the tapestry became a shared energy in the space between where I could almost believe that leaning my weight could cause it to sway in one direction longer. Resonance transpires in this space between where, like contact improv dance, signals are sent at the same time and you cannot say whether you are receiving or giving the impulses.

The dancer Isadora Duncan once said, “I have dreamed of a more complete dance expression on the part of the audience, at a theater … where there would be no reason why, at certain times, the public should not arise and by different gestures of dance, participate in my invocation”.

It is in this same spirit that I made my final interaction in the exhibition. As I moved towards the video projection Kotka₂, I responded to Riitta Vainio’s dance with movements of my own. Instead of just trying to keep up with a mimicry, my movements became a confrontation of the representation of an absent body with my own flesh in blood – a dialogue of mediums. This exchange altered my perception of the video because now I felt its staccato movements in my own body instead of just seeing them as flat images. Perception was no longer resigned in my eyes and brain, but as Belting suggests, an animation, where I was relating to the inanimate object of a wall and projector (transmitting something past), and re-animating it into a live body to communicate with. This interaction then became an event, that “happening” of art in the space between.

I came back to the 16 min video projection₁ and sat on the large black velvety bench that was positioned for its viewing. I tried sitting normally, like I had the first two visits, consuming the video like a movie for my entertainment. Dissatisfied, I decided to recline on the floor and move my hand along it next to me as I watched the hands in the video glide over fabric. My hand felt so alive and an excited energy pulsed through my body. Was it the act of participation in my visual experience or the nerve endings of my fingertips being activated by the texture of the cold concrete floor? Or was it something on a deeper psychological level that I do not quite understand, that happens when you connect to another body with your own, even when that body is only the representation of an absent body, an image being transmitted through a projector? The hand in the video felt like an illusionary or imagined third limb.

When the performer in the video moved to the floor, dangling her head down, I decided to lie on the bench so that my head hung over the edge to view the video upside-down. This was one of my favorite positions – not only was it restful and quite comfortable, it gave me an entirely different experience of this video that by then I had watched all the way through several times. Suddenly, I wasn’t just watching an isolated video that ended abruptly at the edge of its medium body, the panel structure; it began to merge with the floor. I experienced the physical floor like an extended dimension of the video, grounding its visual display in my material, embodied reality.

I realized that my interactions in the exhibition became more like intuitive rituals to reanimate dead objects and summon the spirit of their image into a dialogical dance. The resulting “art” that happened to me then was translated into my body as a memory where my imagination continued this resonant relationship in the living medium of my body. Belting, after likening this process of re-animating dead images to God’s creation of Adam (first formed from clay, then animated with the breath of God’s spirit) writes, “we expect the artist (and, today, technology) to simulate life via images. However, the transformation of a medium into an image continues to call for our own participation”

Based on my experiences, “art” requires two artworks: the art object – the physical material as the body to transmit an image, and a perceiving/animating body – the living medium of the viewer. In spiritual terms, a similarity can be identified here. Much as the material body of an artwork is the means for the spirit of that which it images to become manifest, the artwork of the human body is animated by the spirit of the Divine creator which it images. When these two artworks meet, the images take place in this relational space between. But perhaps it is only in their dance of listening and responding that the “art” happens.

Text: Alyssa Coffin

Video Stills: Salla Ville

Exhibition “Dance! Movement in the Visual Arts 1880–2020” (suom. “Tanssi! Liikettä kuvataiteessa 1880–2020”) at HAM the Helsinki Art Museum 25.3.2022–11.9.2022.

Artworks:

- Sini Pelkki, Departing Shadow, 2021, 16mm film, 16’00”

- Eino Ruutsalo, Kotka, 1962, video, 7’04” (dancer: Riitta Vainio)

- Eino Ruutsalo, Wall of Light, 1971, installation (metal, plexiglass, electric motor, fluorescent light)

- Laila Pullinen, Grand Jeté I, from the Ballet series, 1983, ink on paper; Grand Jeté II, from the Ballet series, 198, ink drawing and ink wash on paper; Grand Jeté III, from the Ballet series, 1983, ink on paper; Grand Jeté IV, from the Ballet series, 1983, ink on paper

- Edgar Degas, Étude de nu pour la danseuse habillée, 1879–80, patinated bronze

- Laila Pullinen, Great Excited Movement I, 1984, bronze

- Sonja Jokiniemi, Work 1, 2022, woven and hand-sewn textile, cotten, merino wool and wool

References:

Rosa, Hartmut: Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World. Polity. 2018

Belting, Hans: Image, Medium, Body: A New Approach to Iconology. Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Winter 2005), pp. 302-319. The University of Chicago Press.

Han, Byung-Chul: The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering. Polity. 2014.

Roseman, Janet Lynn: Dance Was Her Religion: The Spiritual Choreography of Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis and Martha Graham. Hohm Pr. 2004.