Text and photos: Petteri Enroth

In February 2015 I escaped the weather and political climate of Finland into one of the best fantasy-scenarios there is: planning a trip. However, no single European city appeared attractive enough over the others as to prompt a decision about the destination. Finally, like a decent humanist, I decided to combine dulce et utile. Hence, my destination of choice became Frankfurt am Main, the home town of Theodor Adorno (1903—1969), the protagonist of my doctoral thesis, a thesis I still have vague hopes about finishing before I die. The purpose of the trip crystallized into a plan to visit all the city’s sites that played an important part in Adorno’s life, excluding, of course, the time spent in exile in Oxford, New York and Los Angeles.

Surely the idea would have had more substance had the Allied air raids not levelled a large part of the cityscape that Adorno grew up in, specifically the old town and midtown areas. My yearning for an epoch took me first into the Frankfurt historical museum where archaeological objects, collections of art and artefacts, small scale models and animated maps guide the visitor through the city’s historical layers starting with the 13th century. It was quickly obvious that Frankfurt has a long history as a wealthy and tolerant, culturally rich bourgeois stronghold. Collecting art, especially, has been one of the dearest hobbies of the upper middle class, but cultural matters have also occupied a place as the subject of political passions. If one were to choose a single individual to represent Frankfurt, it would perhaps be Leopold Sonnemann (1831—1909), a top-notch businessman, democrat politician, visionary editor in chief of the Frankfurter Zeitung, and diligent patron and collector of art.

I learned that the development of Frankfurt into its present state began with a wave of immigration in the 1500s, when a large number of Dutch practitioners and professionals moved into the city – a quick guess suggests that Frankfurt was situated along important trade routes. Even today, Frankfurt leaves the impression of a historically aware yet modern, liberal and cheerful town where all sorts of people, from impeccably stylish suits to street veterans, walk the same pavements in apparent harmony. Geographically, too, the city is easy to get a grip on. The skyline is dominated by the mid town skyscrapers, earning the city’s nickname “Mainhattan”, whereas the river Main flows through the city from East to West, dividing it into neat halves. On the Northern side one finds, for instance, the railway station and the vivid Bahnhofsviertel surrounding it, the Old Town centre, and, East from the latter, a pretty suburban area organized around atmospheric parks. A few blocks in this residential area attempt to give the impression of a “tough neighbourhood” through graffito and taglines like “fight cops” written on walls, but, at least on an idyllically peaceful Sunday afternoon, it is difficult to avoid the thought that these are the work of sociology students rather than street gangs. The Southern bank of the Main is lined by well over a dozen museums ranging from the Archaeological museum to the Deutsches Filmmuseum, where one can find, for example, an original H. R. Gieger Alien stuntman costume. Heading East, one can contrast the experience of museums with the noisy, fun-loving streets of Sachshausen, and the next day is well spent at the serene hills of Oberrad.

It was this city that, at the beginning of the 20th century, gave birth to the neo-Marxist “Frankfurt School of Critical Theory” that was to have a profound effect on philosophy, sociology and art research. The School’s organizational bedrock was the Institut für Sozialforschung (Institute of Social Research). It was founded by Felix Weil in 1923 to serve as an independent research unit of the young, liberal and also privately funded Johann Wolfgang Goethe University. Weil, heir to his father’s multi-million fortune, generously funded and envisaged a committedly Marxist but academically respectful, scientific research institute and hoped “’one day to present it to a German Soviet Republic’”. [1] Back then, like today, there was not much heavy industry in the city, excluding any glaring presence of a proletariat and its culture. When Max Horkheimer was appointed director of the Institute in 1930, research interests shifted from the history of the labour movement to social-theoretical endeavours with the aim of formulating a Critical Theory of modern societies. Indeed, the fate of the working class is not at the epicentre of the Frankfurt School’s big names: Adorno, Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse and Walter Benjamin. Although the central Marxist concept of alienation was very important to these thinkers, they basically abandoned the idea of the working class’s potential to be the revolutionary subject of history. Instead, the group approached alienation as a broader phenomenon that has less to do with capitalism than with modernization and the conditions that modern societies provide for a subject to form a reality-principle. Given these premises, it is understandable that questions of culture and the arts were central to most Frankfurt Schoolers, especially Adorno.

Early Years in the Mitte and Oberrad

View from the front of Schöne Aussicht 9Adorno’s first childhood home is found in Schöne Aussicht 9, just a couple of minutes walk from the Historical museum in the Southern blocks of the Old Town that overlook the river Main. Friedrich Schopenhauer used to live in the building in the previous century, and in 1903 it became the home of Theodor, the only child of a successful singer of Corsican descent, Maria Calvelli-Adorno, and a wealthy wine merchant, Oscar Wiesengrund. Maria’s devout Catholicism met with an equal embrace of art and culture, which the child absorbed whole-heartedly. Oscar’s assimilated Jewishness and pragmatic take on life, again, remained more distant to his son, although the financial security and tolerant attitude provided by him were important assets for Adorno.

View from the front of Schöne Aussicht 9Adorno’s first childhood home is found in Schöne Aussicht 9, just a couple of minutes walk from the Historical museum in the Southern blocks of the Old Town that overlook the river Main. Friedrich Schopenhauer used to live in the building in the previous century, and in 1903 it became the home of Theodor, the only child of a successful singer of Corsican descent, Maria Calvelli-Adorno, and a wealthy wine merchant, Oscar Wiesengrund. Maria’s devout Catholicism met with an equal embrace of art and culture, which the child absorbed whole-heartedly. Oscar’s assimilated Jewishness and pragmatic take on life, again, remained more distant to his son, although the financial security and tolerant attitude provided by him were important assets for Adorno.

The child received intense nurturing and attention, and great hopes were placed upon him, surely partly due to the fact that five years earlier Maria had given birth to a stillborn baby. In the Schöne Aussicht home the little Theodor – or Teddie, as he was systematically called – browsed the family’s library of sheet music enthusiastically even before he was able to read. He was very fond of playing the piano together with his mother and her sister Agathe, whom Adorno later called his “second mother”. In the evenings the family’s neighbours might have heard Maria and Agathe singing the Lullabies of Brahms and Willem Taubert to Teddie. Taubert’s Lied remained such an integral part of Adorno’s experience that later on he envisioned a whole theory of art built around only this one song. This is a good example of Adorno’s faith that by examining microscopically small details of art and culture it is possible to understand the societal whole from which they arise. Oscar, apparently, was a very engaged and gentle father, but the musical magic circle that Teddie had with his two mothers was quite on another level.

DeutschherrenschuleSchöne Aussicht 9 was bombed in World War Two and rebuilt later. The same is true of Teddie’s first school, the Deutschherrenschule, located on the Southern side of the Main. In the morning, Teddie was escorted by his mothers to the tram stop next to Ignaz Bubis Brücke, across which he then took the tram number 16 to school. The 16-line still exists, and its route is apparently pretty much the same. Out of Frankfurt’s seven bridges, Ignaz Bubis Brücke also remains only one of two that accommodate rail traffic. From 1913 onwards, the same tram took Teddie to his new school, the Kaiser Wilhelm Gymnasium. This building no longer exists, and the school itself was renamed the Freiherr vom Stein Gymnasium in 1945. Still, as the Wiesengrund-Adornos moved from the centre to the cosier area of Oberrad in 1914, tram number 16 remained the most reasonable means of transportation for the boy.

DeutschherrenschuleSchöne Aussicht 9 was bombed in World War Two and rebuilt later. The same is true of Teddie’s first school, the Deutschherrenschule, located on the Southern side of the Main. In the morning, Teddie was escorted by his mothers to the tram stop next to Ignaz Bubis Brücke, across which he then took the tram number 16 to school. The 16-line still exists, and its route is apparently pretty much the same. Out of Frankfurt’s seven bridges, Ignaz Bubis Brücke also remains only one of two that accommodate rail traffic. From 1913 onwards, the same tram took Teddie to his new school, the Kaiser Wilhelm Gymnasium. This building no longer exists, and the school itself was renamed the Freiherr vom Stein Gymnasium in 1945. Still, as the Wiesengrund-Adornos moved from the centre to the cosier area of Oberrad in 1914, tram number 16 remained the most reasonable means of transportation for the boy.

In this new Oberrad home, located at Seeheimer Straße 19, the young Theodor received private education from family friend Siegfried Kracauer, who taught the boy to read Kant’s Kritik der Reinen Vernunft from a materialist perspective and also introduced him to Hegel and Kierkegaard. The young men first met through a family acquaintance, and Kracauer reminisces about his first impression of Teddie in his autobiographical, unpublished novel Georg like this:

He wore a green jacket made from loden cloth which, together with his red tie, was a rough cloak in which he looked like a little prince. Leaning on his mother’s chair, he answered the questions I put to him in a dull tone that contradicted the large, mournful eyes that gazed out from beneath long lashes. Their expression hinted at a mystery that lay hidden in the youth in the same way that he was concealed by the coarse material. [2]

Seeheimer Straße 19Standing in front of the building, it is easy to imagine this teenager, with his precocious fuzz for a moustache, walking down the street toward the tram stop.

Seeheimer Straße 19Standing in front of the building, it is easy to imagine this teenager, with his precocious fuzz for a moustache, walking down the street toward the tram stop.

Precocious indeed Teddie was, and excelled in school. As one might guess, he was not one of the cool guys and faced bullying on a regular basis, especially in the Gymnasium. Later on he even linked this bullying to the ease with which National Socialism was absorbed by the Germans; this sort of sheepish subjection was to be expected from people who “could not put together a correct sentence but found all of mine too long.” [3] Theodor graduated from the Kaiser Wilhelm Gymnasium in 1921 with the highest possible grade, “primum omnium”, and, in the same year, enrolled in the liberal, privately funded Goethe University on the Western edge of the city. A distinctive feature about this university was that it did not shun the newly arisen field of sociology, a field the young Theodor eagerly dug into. During his studies he also met his future friends and associates, the young socialists Leo Löwenthal, Friedrich Pollock, Max Horkheimer and Walter Benjamin, as well as his wife to be, Gretel Karplus. Regarding Adorno’s famously difficult style of writing, academic restrictions obviously could not tone it down. As Kracauer writes to Löwenthal in a personal letter: “If Teddie ever decides to make a declaration of love so as to escape from the sinful state of bachelorhood … he will be sure to phrase it so obscurely that the young lady concerned … will be unable to understand what he is saying unless she has read the complete works of Kierkegaard.” [4]

From Outsider Émigré to Bockheim’s Celebrity

After graduating from Goethe University in 1924, the young man faced a period of oscillation during which he, among other things, studied composition in Vienna under Alban Berg, gained reputation as a music critic in the German music press, wrote one rejected and one accepted Habilitationsschrift (in the German academic system, one step lower than a doctoral thesis) and gave some courses in his home university. In 1934 he was finally forced into exile, during which he first reduced his last name from Wiesengrund-Adorno to W. Adorno and eventually just Adorno.

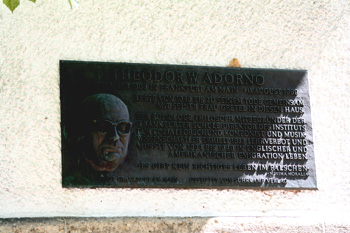

A plaque on the wall of the Kettenhofweg houseThe return to Germany and Frankfurt was not actualized until 1949. Adorno’s wife Gretel arranged an apartment for the couple at Kettenhofweg 123, which is located in the city’s Western area of Bockheim. Gretel was, in general, perfectly dedicated to practical arrangements so as to allow her husband to concentrate on his work. At times she was practically his personal assistant and also ran chores for the Institute of Social Research. Adorno’s reputation began to grow and his status in the post-war academic scene stabilized rather rapidly, thanks to books written during the exile in America: Minima Moralia (1951), Prismen, Philosphie der Neuen Musik and Dialektik der Aufklärung (1947). Today, the Kettenhofweg house is decorated by a metal relief commemorating Adorno’s residence – let it be noted that, as I was addressing the bill with my camera, a girl walking into the building lifted her gaze from her phone and seemed to notice the plaque for the first time.

A plaque on the wall of the Kettenhofweg houseThe return to Germany and Frankfurt was not actualized until 1949. Adorno’s wife Gretel arranged an apartment for the couple at Kettenhofweg 123, which is located in the city’s Western area of Bockheim. Gretel was, in general, perfectly dedicated to practical arrangements so as to allow her husband to concentrate on his work. At times she was practically his personal assistant and also ran chores for the Institute of Social Research. Adorno’s reputation began to grow and his status in the post-war academic scene stabilized rather rapidly, thanks to books written during the exile in America: Minima Moralia (1951), Prismen, Philosphie der Neuen Musik and Dialektik der Aufklärung (1947). Today, the Kettenhofweg house is decorated by a metal relief commemorating Adorno’s residence – let it be noted that, as I was addressing the bill with my camera, a girl walking into the building lifted her gaze from her phone and seemed to notice the plaque for the first time.

The Adornos had a very vivid social life, and pretty much everybody who was anybody in the cultural life of Frankfurt and Germany visited the apartment. However, those who knew the couple well enough knew not to disturb them when Daktari, a US serial narrating the adventures of Judy the Chimp and the cross-eyed lion Clarence, was on TV. From Adorno’s personal letters it is obvious that he liked animals and frequented zoos in his spare time. His favourite animals included the exotic okapi – spotted at the New York Zoo – the rhino and the mammoth. The latter was also Horkheimer’s nickname.

Main Building of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe UniversityThe Adornos’ new home was pragmatically close to the university. The oldest part of the university, the main building that was erected in 1911, is only a few hundred meters away, and diagonally across the street one finds the Institute of Social Research building. Adorno worked at the Institute full-time from 1952, first as associate director, and in 1958 he was appointed director. Today, there is an Adorno Archive in the building with boxes after boxes filled with his official correspondence. When I left for Frankfurt, I did not realize that the archive is not a public library, and the employees of the Institute were a bit perplexed by my emergence in their lobby. However, extremely kindly, the archivist agreed to arrange about 45 minutes for me to poke around the archive room. Even such a short browse made obvious the important part Gretel played: many a letter concerning translations, printing and guest lectures are answered by her. Leafing through the letters, I warmly reminisced about the way Adorno used to handle tedious faculty meetings. I did not manage to find the powwow papers on the archive’s shelves, but in his Adorno biography, Stefan Müller-Doohm writes that in the margins of the surviving papers one regularly finds, not rigorous notes concerning the administrative structures of the university, but drawings depicting a teddy bear (or perhaps a Teddie bear) with a dummy, and a dancer called Marlene. “He would also”, Müller-Doohm carries on, “play around with the text of the agenda, for example changing ‘the establishment’ (Einrichtung) of an office called the dean of studies into ‘the execution’ (Hinrichtung) of the dean of studies.” [5]

Main Building of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe UniversityThe Adornos’ new home was pragmatically close to the university. The oldest part of the university, the main building that was erected in 1911, is only a few hundred meters away, and diagonally across the street one finds the Institute of Social Research building. Adorno worked at the Institute full-time from 1952, first as associate director, and in 1958 he was appointed director. Today, there is an Adorno Archive in the building with boxes after boxes filled with his official correspondence. When I left for Frankfurt, I did not realize that the archive is not a public library, and the employees of the Institute were a bit perplexed by my emergence in their lobby. However, extremely kindly, the archivist agreed to arrange about 45 minutes for me to poke around the archive room. Even such a short browse made obvious the important part Gretel played: many a letter concerning translations, printing and guest lectures are answered by her. Leafing through the letters, I warmly reminisced about the way Adorno used to handle tedious faculty meetings. I did not manage to find the powwow papers on the archive’s shelves, but in his Adorno biography, Stefan Müller-Doohm writes that in the margins of the surviving papers one regularly finds, not rigorous notes concerning the administrative structures of the university, but drawings depicting a teddy bear (or perhaps a Teddie bear) with a dummy, and a dancer called Marlene. “He would also”, Müller-Doohm carries on, “play around with the text of the agenda, for example changing ‘the establishment’ (Einrichtung) of an office called the dean of studies into ‘the execution’ (Hinrichtung) of the dean of studies.” [5]

Vadim Zakharov’s Adorno Monument (2003)In the vicinity of Kettenhofweg one finds, in addition to the Adorno Archive and the impressive Adorno monument by Vadim Zakharov (2003), many things that preserve the cultural heritage not only of Frankfurt, but also of Germany and all of Europe. Within a few blocks one can walk along Dantestra?e, Schumannstra?e, Mendehlssonstra?e, Corneliusstra?e (after the neo-Kantian philosopher, Adorno’s supervisor Hans Cornelius) and wonder at Beethovenstra?e, Beethovenplatz, Hotel Beethoven and, why not, laundry service Beethoven Reinigung. Cleansing as catharsis!

Vadim Zakharov’s Adorno Monument (2003)In the vicinity of Kettenhofweg one finds, in addition to the Adorno Archive and the impressive Adorno monument by Vadim Zakharov (2003), many things that preserve the cultural heritage not only of Frankfurt, but also of Germany and all of Europe. Within a few blocks one can walk along Dantestra?e, Schumannstra?e, Mendehlssonstra?e, Corneliusstra?e (after the neo-Kantian philosopher, Adorno’s supervisor Hans Cornelius) and wonder at Beethovenstra?e, Beethovenplatz, Hotel Beethoven and, why not, laundry service Beethoven Reinigung. Cleansing as catharsis!

Amorbach – Where a Cultural Critic Can Rest

Throughout his life, the holiday resort above all others for Adorno was Amorbach, a small town that gradually arose around a Benedictine monastery in late Medieval Times. No doubt it is this place that was on the philosopher’s mind when he wrote in his Negative Dialektik (1965):

What is a metaphysical experience? If we disdain projecting it upon allegedly primal religious experiences, we are most likely to visualize it as Proust did, in the happiness, for instance, that is promised by village names Applebachsville, Wind Gap or Lords Valley. One thinks going there would bring the fulfilment, as if there were such a thing. Being really there makes the promise recede like a rainbow. And yet one is not disappointed; the feeling now is one of being too close, rather, and not seeing for that reason. … To the child it is self-evident that what delights him in his favourite village is found only there, there alone and nowhere else. He is mistaken; but his mistake creates the model of experience, of a concept that will end up as the concept of the thing itself, not as a poor projection from things. [6]

The village indeed began to seem like a metaphysical promise as getting there appeared to be much harder than I thought. Amorbach? Eyebrows rose as high at the tourist info as they did at the bus station. Anything even resembling a direct connection was not found. I walked to the train station where, waiting for my turn at the ticket office, I overheard two clerks make fun of the hairdo of a customer who had just left. As I was already hungry and frustrated, I did not feel like having to deal with such people, decided to turn around and return the next day. The next morning, I indeed managed to spell the name of my destination to the clerk, and a connection was found – a two hour train ride with two changes.

The Current Building of Hotel PostAs I arrived in Amorbach I could but wonder at the infinitely tiny renown the village had in Frankfurt: with a picturesque medieval centre, the town obviously lives on tourism. The building of the Post House Inn, today known as Hotel Post, where the Adornos by default always stayed, was still there, but apparently closed down sometime around 2010. A heavy cast-iron door handle was covered with cobwebs, the windows were dark, and all in all the place was just an invitation for a little breaking and entering, if only to check out the “Adornozimmer”. Laziness and the desire to avoid contact with Bavarian law enforcement, however, got the better of me.

The Current Building of Hotel PostAs I arrived in Amorbach I could but wonder at the infinitely tiny renown the village had in Frankfurt: with a picturesque medieval centre, the town obviously lives on tourism. The building of the Post House Inn, today known as Hotel Post, where the Adornos by default always stayed, was still there, but apparently closed down sometime around 2010. A heavy cast-iron door handle was covered with cobwebs, the windows were dark, and all in all the place was just an invitation for a little breaking and entering, if only to check out the “Adornozimmer”. Laziness and the desire to avoid contact with Bavarian law enforcement, however, got the better of me.

Everything else in the village was strictly postcard material. Cobblestone streets coiled around cosy taverns. The local market offered shelf after shelf of local Rieslings. At lunch, I was the only customer in an unbelievably idyllic restaurant run by a Sicilian family. Sitting in the courtyard of the restaurant, I could hear nothing but the songs of birds. The pizza was phenomenal, the waiter and I had a nice chat, and I got a free limoncello drink for dessert. I understand Adorno’s attachment to the place, if it was anything like that in the last century. Sipping on my dessert, I recapped an anecdote I had read in some letter by Adorno. As a child, Adorno found a run-down old guitar in the corner of Hotel Post’s courtyard. The instrument was completely out of tune, and Teddie could not play it, but he intuitively grabbed it and was profoundly impressed by the broken, echoing tones. Adorno remembers that this experience formed, for him, something of a paradigm for musical experience. I feel that this memory includes some purposeful colour-correction – Adorno, of course, was one of the most insistent defenders of atonal music – but never mind: the story is very beautiful and relatable.

I also managed to find out the origin of the town’s name. It does not refer to the Roman god Amor, but is a shortened version of a more prosaic name: “am Otterbach” – the “village at Otter Hill”.

On Both Sides of the Philosopher’s Death

Due to technical problems and lack of time I did not manage to visit Adorno’s grave on this trip. A few words about Adorno’s death are in place, though, since it is surrounded by rather unpleasant conditions. During the 1960s Adorno increasingly became the target of criticism from the New Left, that is, from the rising group of student radicals who favoured direct action. His lectures were repeatedly disrupted. An unfortunate event took this schism even further when a group of student activists entered the Institute’s lobby since they had not been allowed into the building they were aiming for. They were simply spending their time and planning what to do next, but Adorno interpreted this as a deliberate invasion and called the police, and the whole thing escalated into a lawsuit and remained a public debate for months. All the while, completing this ironic circle of Adorno’s impossible position, right-wing critics accused him of rousing the student radicalism. After the Spring semester of 1969, the very exhausted and heavy-hearted professor and his wife travelled to Visp, Switzerland for holiday. Despite the doctor’s warnings, the couple made rather trying walks into the mountains, and Adorno suffered a fateful heart attack after returning from one such trip to a nearby village.

Gretel’s reaction to her husband’s death reflects her dedication in a sorrowful way. She took care of the funeral and the necessary paperwork, edited the almost-finished Ästhetische Theorie (1970) for publication with Rolf Tiedemann, and archived letters and unfinished writings. After all was taken care of, she took an overdose of sleeping pills. However, the dose was insufficient, and she woke up in a hospital – or a part of her did. After a brief period at home, looked after by friends, she spent the rest of her life in a mental asylum. In my mind, I go back to the conversation with the Institute’s archivist about the way that the role of women is rather underrepresented in the written history of philosophy.

After one of Adorno’s interrupted lectures in the Spring of 1969, his student, Hans-Klaus Jungheinrich, wrote a newspaper article in the Frankfurter Rundschau with the headline: “Adorno as an Institution Is Dead: How the Consciousness Changer was Driven out of the Lecture Hall”. The point was to defend Adorno against the New Left, whom Jungheinrich considered to have behaved barbarically against the professor. It is easy to agree with this. However, of course, the headline’s claim definitely does not ring true. The tri-annual Adorno award (given to e.g. Judith Butler and Jacques Derrida), the Adorno memorial monument, Adorno archives both in Berlin and Frankfurt, the steadily growing amount of secondary literature… As an institution Adorno is very much alive and one of the most important Continental philosophers of the 20th century. And, of course, this trip would not have been made, and this text would not exist, had I not, in Fall 2006 during my freshman year, grabbed a copy of a recent Finnish translation of Aesthetic Theory published in a temptingly elegant white cover sleeve that radiated with promise.

This text has been translated from an original Finnish blog entry in this webzine; endnotes have also been added.

Notes

[1] Rosa Meyer-Leviné, cited in Rolf Wiggershaus, The Frankfurt School: Its History, Theories and Political Significance, trans. Michael Robertson (Cambridge: Polity, 1994), p. 24.

[2] Cit. in Stefan Müller-Doohm, Adorno: A Biography, trans. Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge: Polity, 2005), p. 38.

[3] Adorno, Minima Moralia, trans. EFN Jephcott (London: Verso, 1974), p. 193.

[4] Müller-Doohm, Adorno, p. 123.

[5] Müller-Doohm, Adorno, p. 468.

[6] Adorno, Negative Dialectics, trans. E. B. Ashton (London: Routledge), pp. 373—74.