The documenta exhibition was organized in Kassel for twelfth time this year. This festival of contemporary art is a spectacle, and it has also become a source of controversy for the local inhabitants. I can imagine, that getting into the limelight of art world every fifth year creates a twofold identity for the local people. Money comes pouring in for one reason only – so that the trendy art people can quickly visit the city and come back after another five years. The exhibition vitalizes the city of Kassel, but good grief, if one should live there during the intermission years.

Because this was my first visit to the documenta, I was embarrassed to report a young woman working on a survey of visitors, that the only thing I know about Kassel is the documenta. It is the only reason for me to come there. Even though the city is in the middle of Germany it still is in fringe.

Spectacular!

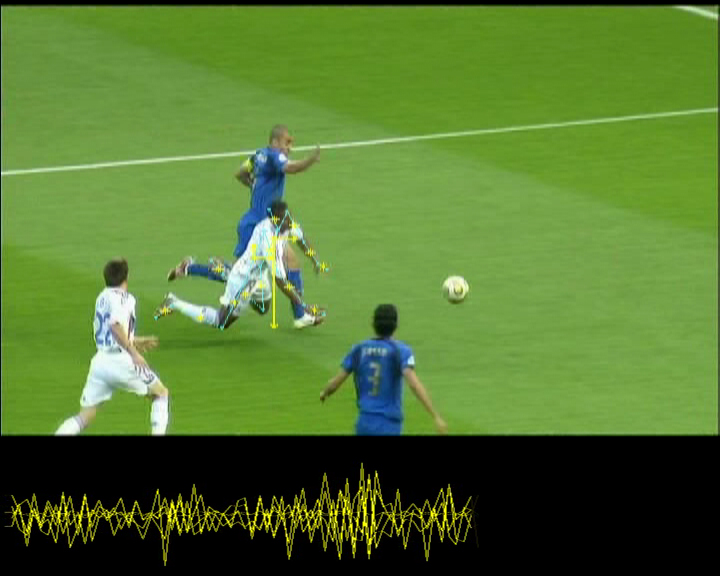

The first work of art, which really caught my attention, reveals something of the documenta, too. It was not Sanja Ivekovi?’s “Poppy Field”, which caught my eye; a work connected with Afganistan and oblivion situated on Friedrichsplatz, situated right in front of the main exhibition hall, Fridericianumin. Instead I was stopped dead by Harun Farocki’s “Deep Play”, a video installation presenting the football World Cup final, between France and Italy in 2006.

Harun Farocki, Deep Play (2007)

Harun Farocki, Deep Play (2007)

Harun Farocki, Deep Play (2007)

Harun Farocki, Deep Play (2007)

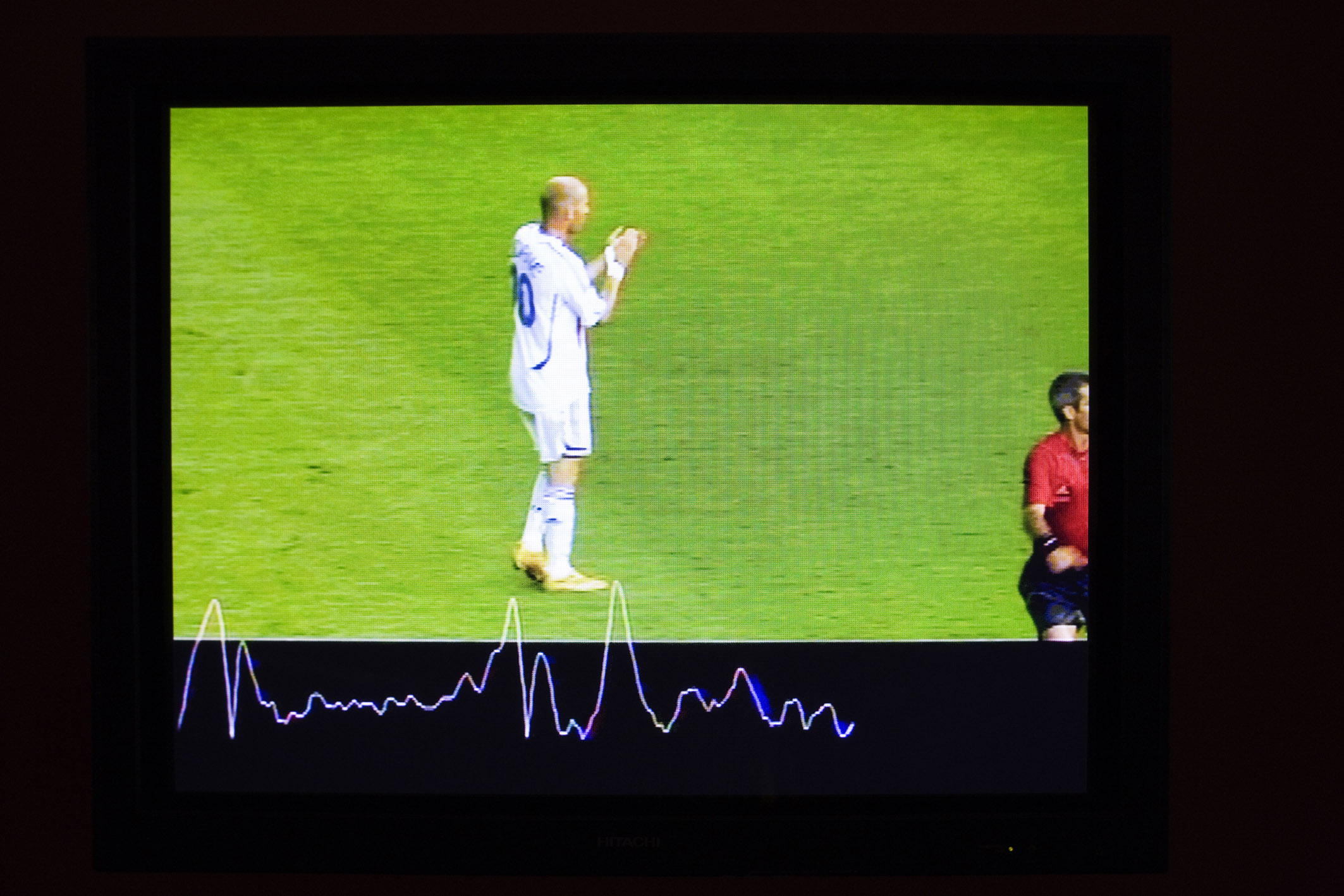

Farocki is one of the most famous names in experimental documentaries in Germany. Few years ago his work was also seen in the Avanto festival in Helsinki. “Deep play” displays various points of views about the passion laden soccer spectacle. The France–Italy game has been fragmented into pieces, so that 12 televisions show camera clips of the coaches, and the game, we also hear the director’s orders, see player diagrams, computer simulations and analyses, we are shown glimpses of the stadium police working, the summer night outside the stadium in Berlin… and a computer animation of Zidane’s head butting right into Materazzi’s chest.

Zidane’s head butt made the championships game unforgettable and a source of enormous speculation. Why would a player on the top of his career, in his last game do it? Would various different analyses help us to understand better what happened? Was it justified in any way, or did the star player adored by the French stain his reputation for the rest of his life? Did Zidane, a son of Algerian parents, and a child of the streets of Marseilles, show his true colors? Those defending Zidane were claimed to accept violence, while those who stood up for Materazzi were considered as hypocrites taking the winner’s side. (It was Italy who won the game.)

”Deep play” may almost appear as a textbook example of how one can deconstruct or take a spectacle in pieces. At the same time it reveals the power of media and how the flow of images directs our impressions. Earlier on Farocki’s name has been connected with Paul Virilio’s thinking.

As a viewer I was thinking on one hand about the capability of a spectacle, such as football World Cup, to provoke passionate reactions: the one and same transmission had 1.5 milliard spectators all around the world. On the other hand I was reflecting about my own experiences as a documenta visitor. The documenta is a spectacle, which bears similar characteristics as the famous football final. At least people use their time and energy to travel to Kassel, the critical eye is focused on the works, artists and curators. Newspapers publish reviews, which are read by those who saw the show, will see the show and also by the ones, who do not visit Kassel, but are supposed to follow discussions about the documenta of the year. When the cameras are focused to what seems to be important, everything else, for which one has no time, energy, or interest in is left in the dark.

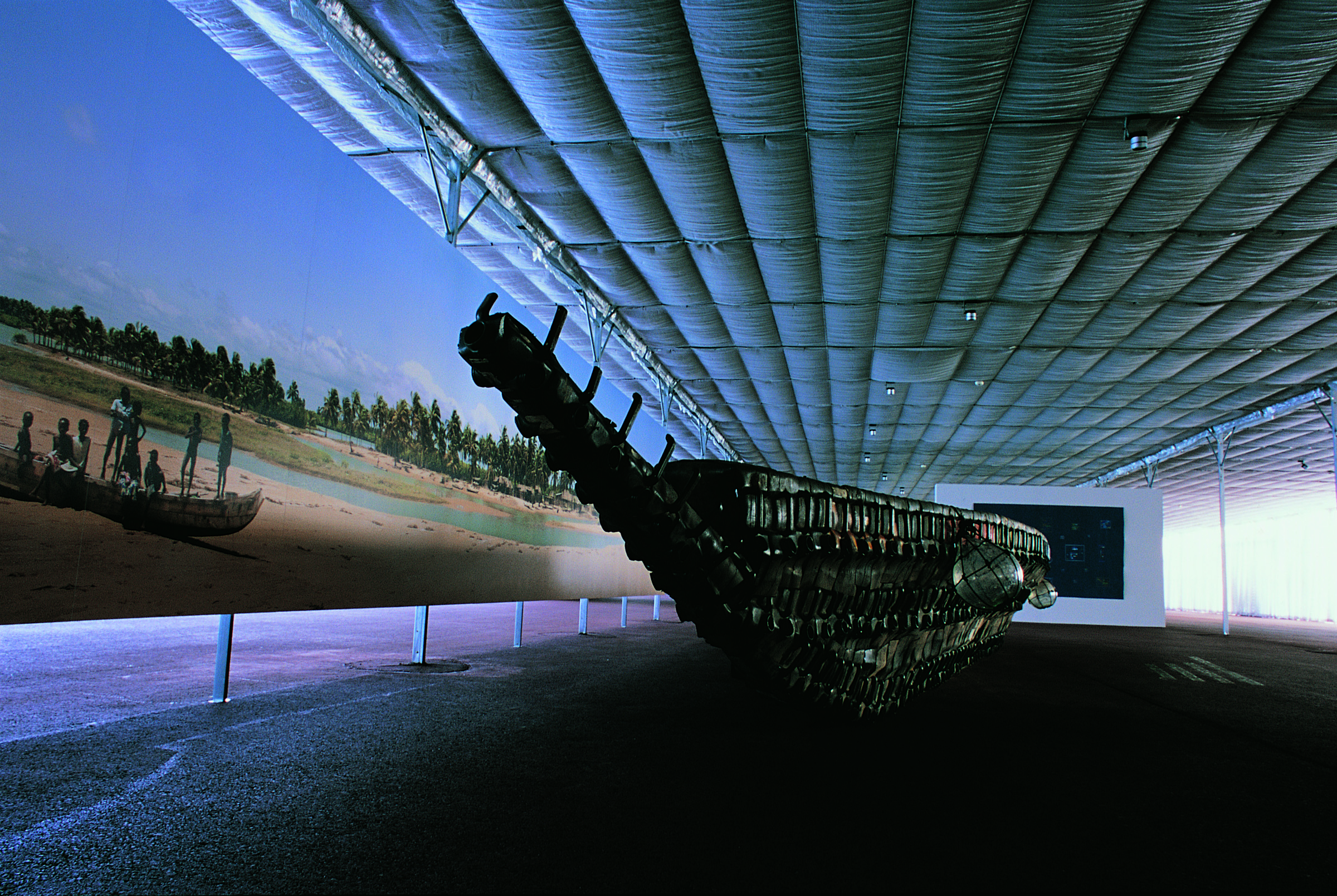

There are many art works taht connect to the afterthoughts of Farocki’s work. For instance, Benin based Romuald Hazoumé’s installation “Dream”, or Danica Daki?’s “El Dorado”: consisting of a video installation, a performance and a guided tour. Hazoumé’s work was exhibited in the Aue-pavilion, a greenhouse-like space designed for the documenta, which merely helped to protect the works of art against the rain. Hazoumé has been working for some time now with canisters. In Benin they are used, among other things, for smuggling fuel. “Dream” consisted of a big dark boat build of canisters without cork and of an image showing a paradise like beach. The word ‘Dream’ was painted on the one side of the boat.

Romuald Hazoumé, Dream (2007)

Romuald Hazoumé, Dream (2007)

Sarajevo born and Düsseldorf based Daki? takes the visitors to the German Wallpaper Museum, which also hosted the two other parts of the work, the performance and the artist’s guided tour. Unfortunately my visit to Kassel was so short that I did not have time for the Wallpaper museum – characteristic of my visit – I only saw the video and photograph in Wilhemshöhe Castle. The work was done in co-operation with a local organization helping under aged unaccompanied refugees, a local youth cultural center, and a dance school. Even though some seasoned Kassel traveler might have smelled here an attempt to compensate the claims according to which the previous Documenta was too detached of the city and its people, Daki?’s work paid successfully attention to people and their lives, that the visitors would have otherwise omitted. The German Wallpaper museum hosts a luxurious El Dorado panorama wallpaper from 1848, which elegantly depicts different continents through architecture, flora and fauna. In Daki?’s video young people move around, dancing, running, training, in the landscapes of El Dorado and Bauhaus wallpapers.

Danica Daki, El Dorado (2007)

Danica Daki, El Dorado (2007)

Both Hazoumé’s and Daki?’s pieces make the spectator think about the differences between those various dream worlds that direct streams of people. El Dorado is a myth transformed during centuries, it refers basically to an ancient Southern American golden city. The story was spread to the west by Spanish conquistadors. Those who are heading to Europe now, do not know about golden cities, and only a few make it to the limelight from the prop. In spite of this a young immigrant boy says decisively in Daki?’s video: this is only the beginning.

Behind you / look ahead

This year Kassel also was about thinking back. Artistic director Roger M. Buergel and curator Ruth Noack reminded that the documenta was originally founded to enlighten the German audience about modern art. In the aftermath of the Second World War there was urgent need to update the German’s sense of aesthetics, as well. The choice of Kassel as the exhibition city was related to the representational nature of it: Kassel was heavily bombed during the war and its city center has been almost totally rebuilt in the 1950s.

The first of the three main themes of the documenta: Is modernity our antiquity? Originates in this historical perspective. The exhibition asks what is our relationship to modernity. History and remembering also are present in the exhibition spaces. There are many works from the 1960s, like American Agnes Martin’s painting, but also much older works: Japanese Katsushika Hokusai’s is included with a work that presents Hokusai’s variations of traditional ornaments which was meant to be used by other artists and artisans. This piece from 1835 is confusingly modern: “Hokusai made bar codes”, comments one visitor.

The two other thematic questions of the exhibition were: What is bare life? and What is to be done? Former question is made in the spirit of Giorgio Agamben, who has asked: what if political community would not base on the figure of the citizen but on the refugee? The latter question discusses the role of art and aesthetic experience in all this. The question reaches out towards art education, which played a significant part in this year’s documenta, not only one minor side issue.

Globalization and the streams of migrating people challenge the modern western democracy. What is left for contemporary art to do? Buergel and Noack have been searching for answers in dialogue with the art world: nearly 100 magazines or internet-publications were invited to participate in the discussion before the exhibition and while it was ongoing. The results of the project can be read from net publication as well as from three documenta magazines (books, really): Modernity?, Life! and Education. This vast, if not exhausting, project lead by Georg Schöllhammer was participated by prestigious magazines such as Le Monde diplomatique (Berlin) and Third Text, but also, as described in the press release, smaller publications from smaller language areas, further away from the center of the art world. Estonia’s kunst.ee, Sweden’s Glänta and Site Magazine, Russia Moscow Art Magazine and Chto delat?/What is to be done? Were presented from Finland’s neighborhood. Unfortunately no Finnish art magazine was seen listed.

The politics of visibility

After visiting the documenta I read the exhibition reviews against my own perceptions. The reviews of Le Monde, Guardian, Spiegel, Dagens Nyheter, and New York Times repeatedly commented that the exhibition was difficult, disastrous, heavy, though occasionally question raising, the works were visually poor etc. One of these repeated comments dealt with the absence of so called big names.

As a first-timer I cannot say what the exhibition should have been like, but I would not call it catastrophic. What is a visually impressing is an ambitious notion. I circulated in the exhibition space without a clear pre-exiting intention to write about it – this text is thus based on somewhat light-hearted observations – and yet there seemed to be many works, which impressed me with their very visual nature. I had to ask myself, where was the modest and quiet that I did not remember nor had the time or energy to think about? Even though the exhibition did miss a strong star representation, the participators were far from nobodies. For instance, American choreographer Trisha Brown and artist Mary Kelly are professionals with a long career, whereas the works of duo Dias & Riedweg and Israeli born Yael Bartana have been familiar sights in European museums.

The exhibition is openly political – and politics is taken seriously. This can be justly considered to be heavy. From my own wanderings I can remember only few works that spoke with lightness or humor, such as Bulgarian Nedko Solakov’s “Fears”, series of 99 drawings describing embarrassing, sheepish, painful or absurd situations. It is naturally easy to pass by those works one considers to be deadly. Of course, what is considered to be boring or deadly is a matter of taste. If one understands politics as a politics of visibility, one interesting work in this perspective is Lu Hao’s paintings of a Bejing street.

LU HAO, recording chang’an street (2005)

LU HAO, recording chang’an street (2005)

Bejing is experiencing severe rebuilding, the goal of the officials is to polish the city for the Olympic games in 2008. Whole blocks are being demolished for the new massive buildings. Lu Hao, who uses traditional realistic Chinese painting style, has taken as his commission to record the transformation of the city and. The documenta exhibits Lu Hao’s Chang’an Avenue. The street has been used for military parades, as it cuts through Bejing, bypassing the Tiananmen Square, National Theater and museum. Lu Hao’s work could be paired with with a work of another Chinese artist Ai Weiwei wherein doors and windows have been piled on the yard of Aue-pavilion. These doors and windows originate from ancient demolished houses from Ming- and Qing-dynasties.

Another work named “Phantom Truck” addresses the politics of visibility to the letter. It belongs to Spanish born Inigo Manglano-Ovallo, who lives now in the United States. In the furthest and darkest corner of documenta -hall there is something big, which slowly, as one’s eyes get used to darkness, appears to be a truck trailer without a cover, as in X-ray. Inside the truck trailer one can see some details, such as gasholders. The work is a reconstruction based on the descriptions of vehicles for producing biological weapons, which United States claimed to be found in Iraq and which served to justify the war in Iraq. Afterwards no proof of these factories was found.

When it comes to politics a Berlin based artist Hito Steyrl moves in a more personal and in my mind more interesting level. Her work called “Lovely Andrea” takes its point departure in the Japanese sexual bondage tradition. A few years ago Nobuyoshi Araki’s exhibition in Tennis Palace Art Museum in Helsinki introduced to Finnish people this subgenre of pornography originating from martial arts and the artful use of twine and tying up one’s enemy. Steyrl is known both as video artists and theoretician. Her work often challenges the traditional conceptions of a victim and an evildoer, what is morally right and wrong. In “Lovely Andrea” Steyrl is searching after a bondage picture taken of her in Tokyo in 1987 and thus happens to visit several bondage photographers. The work touches some intriguing themes, such as how to track down a single nawa-shibari photo while the photographer is unknown and the whole matter was, at that time, part of censored imagery? The encounters with the former model, the still practicing photographer veterans, and their apprentices reveal interesting power relations and attitudes in Steyrl’s montages. Bondage is also seen as a metaphor when it is connected with Spiderman and Guantánamo prisoners.

Hito Steyerl, Lovely Andrea (2007)

Hito Steyerl, Lovely Andrea (2007)

Off guard I find myself thinking of Monika Baer, German painter whose large “Vampyr”-paintings seduced me to their surreal, floating world. Baer’s small scale painting titled “Ten dollars in a state of disintegration” appears to be playing with dimensions: it is as if the spectator was witnessing the passing of a shabby buck into another reality. Painting’s bill intertwines with the movements of money, the lack of it and relativity of it.

In conclusion

The documenta can be reproached as an exclusive institution in spite of its awareness and willingness for a dialogue. As an institution, it always holds the power to exclude something: be it a majority of today’s “A-list artists”. Challenging the traditional hierarchies will not free the documenta from itself. One can blame that the exhibition is even poor: either the masses or the experts did not get what they wanted; either the works were boring or the concept was too theoretical, and either its connections to the works were too obvious or too loose… The spectator can always do what the artistic directors Buergel keeps talking about: to concentrate to art.