Scrolling through gay dating platforms, one is confronted with an alarming number of profiles that state disclaimers such as: No Femmes, Masc4Masc, and/or No Asians, Browns, and Blacks. Often accompanied by No Fats. Essentially suggesting that the ideal body type is masculine, fit, and white. Despite the fact that in 2019, with shows such as Pose (Murphy, Falchuk, Canals, 2018) there is a larger representation of diverse LGBTQ+ characters on television than ever before (Elber & Press, 2019), and we are seeing more vocal perspectives from trans and non-binary folks (for example Alok Vaid-Menon, Jonathan Van Ness, and Vivek Shraya) in media and the arts, prejudices based on body image and masculinity, as well as racism remain significant issues within the gay community.

Following the so-called European Migrant Crises, and the general anti-immigrant and Islamophobic sentiment in the region, exclusionary politics within mainstream gay culture became further exposed. For example, in Helsinki, the capital of Finland, in 2017, two gay clubs (DTM and Hercules) were accused of racism and Islamophobia when a pattern of rejection – specifically targeting non-white immigrants – became apparent at the entrance of the venues as well as the fact that a racist article was shared on the official social media page of Hercules (Qureshi, 2018). Similarly, in Central London, Rohit K. Dasgupta and Debanuj Dasgupta highlight issues encountered by a “queer Muslim working-class gay man,” and his rejection from a gay bar, arguing that “the formation of the queer Muslim racialized subjectivity is a spatialized process one that situates queer Muslims on the peripheries of gay (white) spaces” (DasGuptaa & Dasgupta, 2018).

Extending this discourse further, where gay white identity forms the center, I analyze Tom of Finland and the French porn filmmaker, Jean-Daniel Cadinot, unpacking the visual construction of gay masculinity, and histories of fetishization and representation of bodies of color through a white lens. Thinking from a Muslim perspective, and to counter and reverse the dominant positioning of whiteness framing gay identity, I discuss Mussalmaan Musclemen, a series of artworks by San Francisco-based Pakistani / Lebanese artist, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (b. 1990) as a way forward.

Tom’s Men and Cadinot’s Harem

Touko Laaksonen (1920–1991), more commonly known as Tom of Finland, is known for his sexually charged and highly fetishized illustrations of men engaged in homosexual activities. Laaksonen launched his career in the 1950s, approximately two decades before homosexuality was decriminalized in Finland. Fearing prosecution in his own country, he primarily presented his work in the U.S. print market (Paasonen, 2019). Within his work, Laaksonen drew “influences from the uniforms of Third Reich soldiers, U.S. street patrol officers and motorcyclists into a fantasy fabric occupied by almost photo-realistically rendered, yet physically impossible male bodies exaggerated in their extraordinary physique” (Paasonen, 2019). Looking at Laaksonen’s drawings today, especially from the perspective of critical and intersectional queer theory, a few problematic aspects that immediately stand out include an unrealistic idealization and representation of masculinity and eroticization of the uniforms – which are loaded with a violent history, as well as the depiction of black bodies. According to Guy Snaith, “Tomland is a fantasy world in which masculinity is held up as the highest ideal, in which it is the most natural thing in the world for virile men to be attracted to other virile men in public” (Snaith 2003). In many ways, this glorification of machismo emerged as a result of effeminate gay men seen as negatively – which Laaksonen forcefully challenged by presenting gay men as manly, and created the possibility to “eliminate gay guilt, to correct injustices, to validate gay men, their desires and their experience” (Snaith 2003). Many men at the time described experiencing Laasonen’s images as a liberating, and allowing them to be “more comfortable with who they were,” and referring to themselves as Tom’s men (Pohjola 1991).

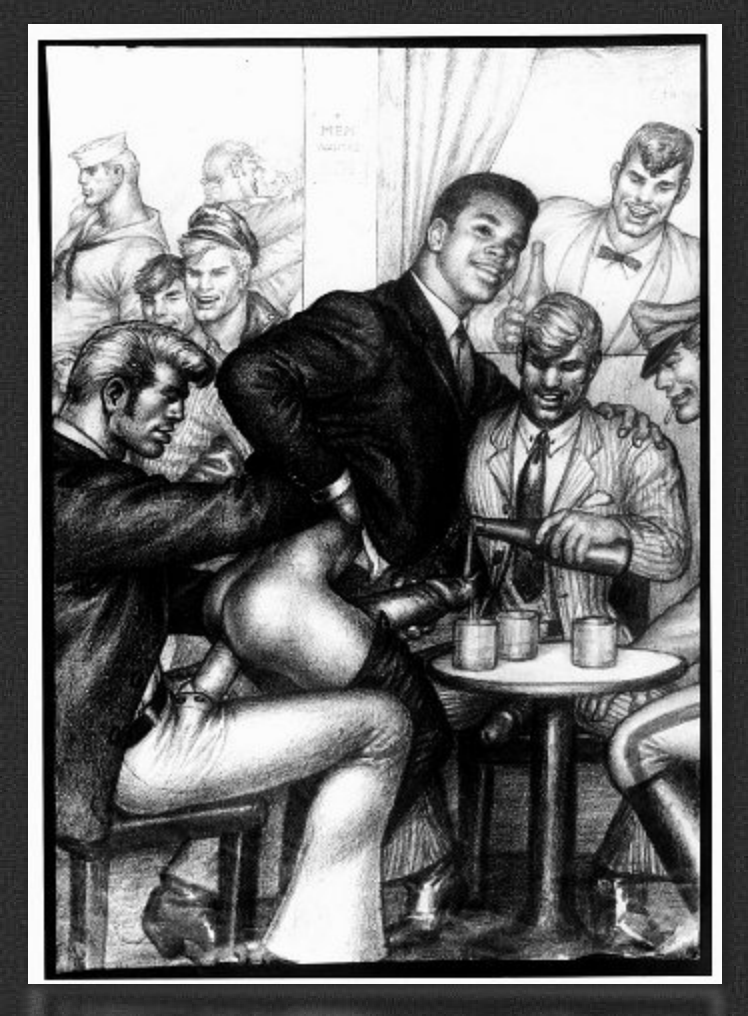

On one hand, the depiction of macho men and uniforms engaged in homosexual activities, actively or voyeuristically, can certainly be interpreted as subversive, mocking and undermining the power patriarchy wields in history by causing ruptures in traditional notions of masculinity and gayness (at that point in history). At the same time, however, it is also important to acknowledge that the lens of depiction in Laaksonen’s case is racially white, and that itself carries power, such as we see through his representation of black sexuality. The white gaze in its active form, as explained by George Yancy (2016), is “implicative of a site of white power, hegemony, and privilege, one that comes replete with an assemblage of ‘knowledge’ or a racist episteme regarding the Black body” (Yancy 2016). For instance, looking at Laaksonen’s drawing above, which is one amongst many, we see a black man being anally penetrated by a white man, another pouring a drink on his penis, while others in suits and uniforms (except for a sailor and the couple kissing in the back) watch enthusiastically. The black man is smiling, looking in the distance, and perhaps enjoying being the center of attention (of white men). Both men who are engaged in the sexual activity have magnified penises, which in Tom’s vocabulary, is most likely a compliment, as Julien Isaac, the British artist, and filmmaker, has observed (Pohjola 1991). On the surface, this image by Laaksonen, as well as others where the roles are reversed, where you see white men being penetrated or worshipping black men, some may even see the representation of bodies of color as progressive. However, when reading such images, it is not possible to detach the long history of slavery, violence, and segregation against black communities in the United States – some of which continue to this day in the form of police brutality – and consume these portrayals for mere pleasure. Furthermore, it can be argued, given Laaksonen’s influence on contemporary gay culture as observed by Robert Mapplethorpe (Pohjola 1991), that his portrayal of masculine gay men, and complete absence of effeminate gay men, has an explicit link with the reduction of space for, and even marginalization of, femme, trans, and non-binary folks in the gay today.

Another example of someone who problematically uses the representation of masculinity and bodies of color from the position of whiteness is Jean-Daniel Cadinot. While in the active role, as is much clearer in the case of Laaksonen, ”white gazing is a violent process” (Yancy 2016). When we look at Cadinot, we see a more complex form of white gazing, where he depicts the white boy being dominated by bodies of color, playing on racial and colonial stereotypes of black and brown bodies. In this instance, “white gazing is a deeply historical accretion, the result of white historical forces, values, assumptions, circuits of desire, institutional structures, irrational fears, paranoia, and an assemblage of ‘knowledge’ that fundamentally configures what appears and the how of that which appears” (Yancy 2016). The films, Harem (1984) and Chaleurs (1987) make good examples to illustrate this point. Harem begins in a general bazar setting in North Africa, with generic Arabic music playing in the background. The story follows the day/journey of a young and blonde French boy, who is petite and has a mostly hairless and slim body. As he walks through the market, entering different shops and hammams (traditional bathhouses), he encounters a range of more dominant and aggressive Arab and African men – who taken over by uncontrollable lust at the sight of this white boy, all, one by one, enter him during the film. Similarly, in Chaleurs, Cadinot presents another petite and blonde boy, this time German, wearing a safari suit, getting lost in the desert. During the sandstorm, he seeks refuge at the tent-like homes of the natives, where he is raped each time. In the instance, where two locals are engaged in consensual sex (as a result of being aroused having seen the white boy used and abused), the background carries the sound of Azaan – the Islamic call for prayer, further suggesting that the bodies of color depicted are, in fact, Muslim, or at the very least, situated within a pre-dominantly Muslim context.

At various points, both, Harem and Chaleurs, use colonial tropes of representing bodies of color. For example, ominous music plays when the timid and delicate French boy enters a tent or a shop and is about to be violated by tribal and savage brown and black men. We can analyze Cadinot’s portrayal through the idea that ”whiteness deems itself un-raced and universal”, and built within that is the lie that “the Black body is night, doom, darkness, and danger; it is deceptive and devious; it is a site of vice and moral depravity” (Yancy 2016). Extending Yancy’s line of thinking, we can then deduce that danger to the white boy is that through the act of being penetrated, his whiteness, thus his purity, is about to be polluted.

Mussalmaan Musclemen

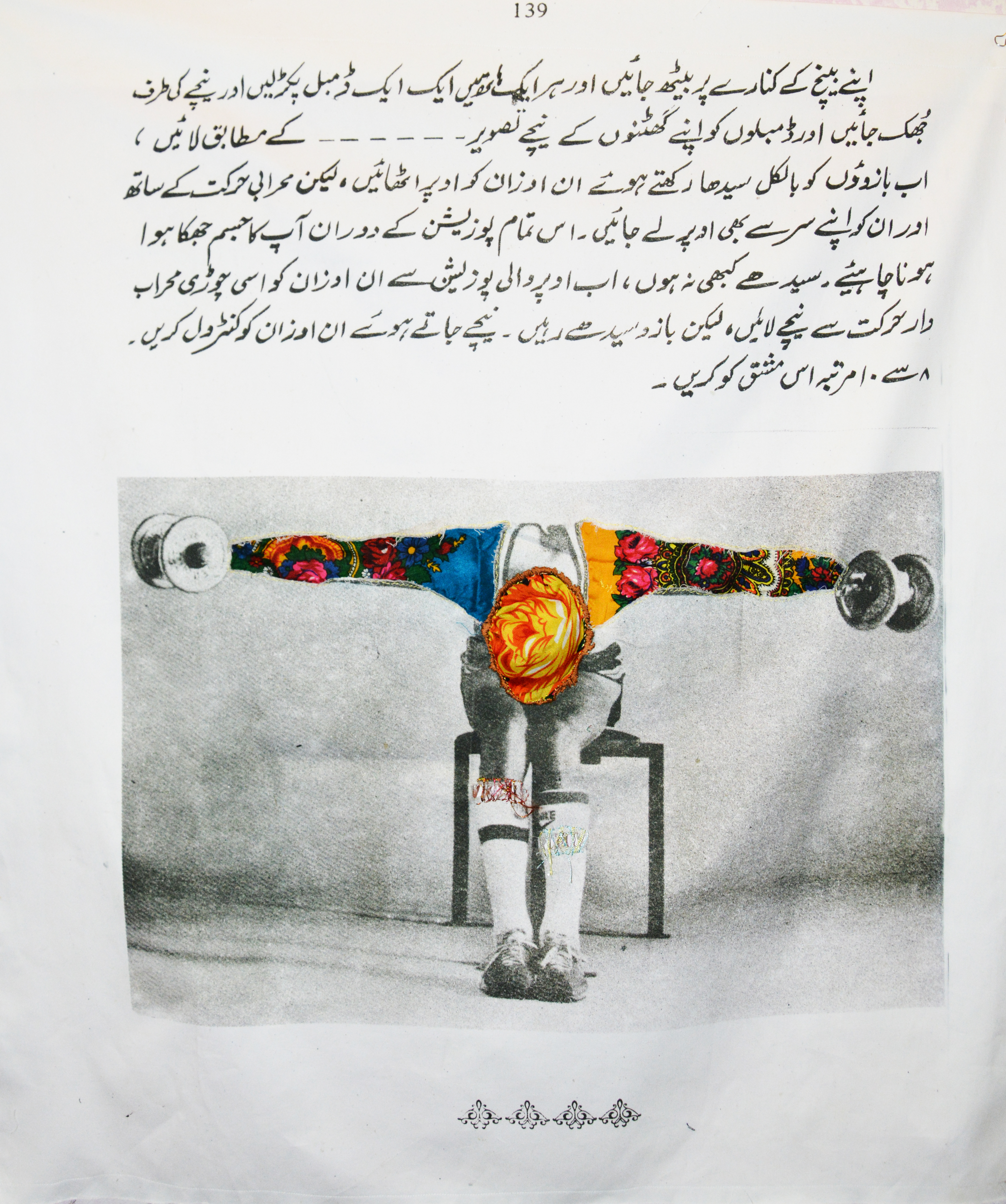

A challenge to this history and legacy of white gay men representing, or using, black and brown bodies as mere objects of their fantasy, can be seen in the works of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Through his multidisciplinary practice, Bhutto examines issues of identity and histories of colonialism, particularly in relation to current political systems and regimes, through the perspective of queerness and Islam. In his series, Mussalmaan Musclemen, a textile-based body of work that comprises of digitally printed images of bodybuilders – who mostly read as white – on loose pieces of cotton as well as a book format made of fabric pages. The printed images are laced with patches of embroidery, crochet, and bright, multi-colored, South Asian fabrics with floral patterns and paisley designs.

Speaking about the series, Bhutto contextualizes Mussalmaan Musclemen as a body of artworks that address issues of masculinity, which within the context of post-colonial South Asia constructs the man in a specific way. Elaborating on this, Bhutto writes, that growing up, for him, ideas of masculinity in Pakistan “relied on strength, dependability and hardness with softness being a sign of weakness, of being less than manly” (Bhutto, 2017). In Pakistani visual culture, perhaps, frameworks of masculinity are best illustrated by taking a look at films from the Punjab region (on the eastern border of the country), where films such as Maula Jatt (Malik, 1979) – featuring Sultan Rahi (1938–1996) – depicting good men against evil, violently seeking justice or revenge, frame perceptions of masculinity.[1] For Bhutto then, to employ the act of applying a craft widely considered feminine in South Asia today, can be read as queering notions of manliness – where the overly macho men are decorated, layered, or veiled with delicate motif prints.

On technique, Bhutto talks about the act of stitching and applying patches on these men – sometimes manually with a needle and thread, and at others using a sewing machine – as flaying, medical skinning of the bodies, which results in a “Frankenstein effect” (Bhutto, 2017). However, the puncturing and patching of colorful fabrics on the muscled bodies (that read as white), can also be seen as a reversal of the violent white gaze; this time a brown body striking back – leaving traces on the vibrant satin that covers the back of the panels.

Bhutto’s investigation into these muscled men began with a chance discovery of a bodybuilding manual, apparently authored by Arnold Schwarzenegger, which had been translated into Urdu. This find also coincided with Bhutto’s on-going photographic research and exploration of all-male spaces in Pakistan, in particular, an akhara (traditional wrestling training ground and school) in the Walled City of Lahore and malakhra (ancient form of wresting) in Sindh, where he captured blurred and sweaty images of men. In these pictures it is unclear whether the bodies are in fact wrestling, or simply locked in strong embraces that could also be read as sexual. Even though homosexuality is still criminalized under section 377 of the Pakistani Penal Code, an inherited colonial law, of course, many gay and queer encounters still occur throughout the country.[2] Outside middle and upper-middle-class bubbles in the larger cities, a lot of times, these encounters occur in a way that would be best be described as cruising – in public parks, old cinemas, and indeed near akharas, where once the wrestlers are done training and would like to blow off some steam, sex happens in dark alleys, perhaps empty storage rooms, or whatever may serve the purpose. With this context in mind, Bhutto’s use of these muscled figures begins to open a window into a culture of gayness that so far does not inform gay discourse in the West, directly confronting the racist legacies of Tom of Finland and Cadinot in contemporary gay culture.[3]

Conclusion

Reflecting on the past, and thinking about an age when homosexuality was still criminalized in most parts of Europe, and dialogue on critical race was minimal, the works of Laaksonen and Cadinot may have appeared as a radical way forward, not only depicting forbidden sex but also including bodies of color. Today, even though many conversations on decolonization are well underway, a lot still needs to be done. As geographies continue to change due to a consistent flow of migration, we also see reactionary policies and closing of borders, for example through the Muslim Ban by the United States of America and BREXIT in the United Kingdom. In such exclusionary times then, I believe, it is imperative that the gay community does not mimic similar refusals, and starts questioning problematic parts of its history through an intersectional perspective opening up to different forms of masculinity as well as diverse bodies.

I am also aware that perhaps the length of this text is not sufficient to discuss the full complexity of many of the issues around gayness, masculinity, and race that I have addressed. I hope to continue this investigation, and write about it further in the form of a chapter in my doctoral dissertation.

As a way of concluding, I would like to do so with a speculative thought. Within Islamic history, Zulfikar was the name given to the sword of a mighty warrior – and though the literal meaning in Arabic is unclear, some interpretations of the word Zulfikar point to Lord or Master of. Combined then with Mussalmaan Musclemen, Bhutto becomes the Lord/Master of Muslim Musclemen, providing an alternative to Tom’s men, and taking an alpha role to unsettle and reverse frameworks of masculinity, which as a sensitive or an effeminate young boy, he felt outside of. Thinking of José Esteban Muñoz (2009), where he states, “Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality.” – I say, with Zulfikar’s Mussalmaan Musclemen we have a potentiality, and I hope we can continue to think of more.

Text: Abdullah Qureshi

References

[1] In the case of Maula Jatt, the story, which is set in rural Punjab, begins with the gang rape of a woman by a powerful clan who nobody would speak or stand up against. Desperate to seek help, she reaches Maula Jatt, who threatens the rival clan, seeking justice by proposing that the girl should be married to the principal rapist, and the clan’s leader’s sister should be married to the raped woman’s sister. For a more complex reading of masculinity, as well as other gender and class-based issues in Punjabi cinema look at Gender roles in Pakistani films: How a male is represented in Pakistani cinema (2015) by Sevea Iqbal.

[2] It is worth clarifying here that apart from select middle and upper-middle-class circles in the larger cities of Pakistan, gayness and queerness does not operate, nor is it understood the same way as we discuss it in the West. For instance, some folks invested in critical discourse reject the term ”gay” as colonial terminology. Whilst others discuss the lack of local language to express gay and/or queer desire/love/sex. Additionally, as is evident through the work done by non-governmental organizations that provide LGBT sexual health support, for example NAZ Pakistan, reveal that a significant number of men who have sex with men, continue to also lead ‘normal’ married lives.

[3] Having said this, it is important to state that Bhutto is not the first artist to be looking at this culture in Pakistani contemporary art. References and representations of the wrestlers of Lahore, as well as the cruising culture, though not contextualized as such, are visible in the paintings of Anwar Saeed (b. 1955).

Bibliography

Bhutto, Z. A. (2017, June 5). Mussalmaan Musclemen: Dissecting Masculinity In Pakistan Through Art. Retrieved November 21, 2019, from Huffington Post: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/mussalmaan-musclemen-dissecting-masculinity-in-pakistan_b_5935be64e4b033940169cd09

DasGuptaa, D., & Dasgupta, R. K. (2018). Being out of place: Non-belonging and queer racialization in the U.K. Emotion, Space and Society (27), 31-38.

Elber, L., & Press, T. A. (2019, 11 7). LGBTQ Characters on Network TV Hit a Record High, Study Finds. Retrieved 12 21, 2019, from Fortune: https://fortune.com/2019/11/07/lgbtq-characters-network-tv-glaad-study-pose-batwoman/

Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press.

Paasonen, S. (2017, November 8). Many splendored things: Sexuality, playfulness and play’. Sexualities , 21 (4), pp. 537 – 551.

Paasonen, S. (2019). Tom of Finland comes home, keeps on coming. Porn Studies .

Pohjola, I. (Director). (1991). Daddy and the Muscle Academy [Motion Picture].

Qureshi, A. (2018). Queer Migrations: The Case of an LGBT Cafe/Queers without Borders. In A. Suominen, & T. Pusa, Feminism and Queer in Art Education (pp. 91 – 115). Helsinki: Aalto ARTS Books.

Snaith, G. (2003, March/July). Tom’s Men: The Masculinization of Homosexuality and the Homosexualization ofMasculinity at the end of the Twentieth Century. Paragraph , 26 (1/2), pp. 77-88.

Yancy, G. (2016). White Embodiment Gazing, the Black Body as Disgust, and the Aesthetics of Un-Suturing. In S. Irvin, Body Aesthetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Corrected to the text 16.3.2025: The boy in the film Chaleurs is German, not French.