Text and photos: Nikolai Sadik-Ogli

Born in 1903 in St. Louis, Missouri, Walker Evans is the older of two major American artists whose works are currently on display at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Lacking any subtitle and featuring over 400 items, Walker Evans represents the first complete retrospective of this interesting photographer’s rich career. The exhibition begins with his first touristic snapshots of Paris, where he travelled in 1926 as a student and translated important French literature, such as Charles Baudelaire and Blaise Cendrars, into English. The most compelling pictures from this period are the self-portraits that Evans took in various settings, including some shadowy silhouettes. This interest in ‘selfies’ continued after Evans returned to America, where photobooths had become common, and a good example of his enthusiastic use of these amusements can be seen in the Three Self-Portraits (1927) that can be seen on the exhibition poster above. The experience of documenting his own exaggerated displays, as evidenced in the picture on the far right, inspired Evans to specialize in photography.

These examples of taking self-portraits and using cheap photobooths along with an almost random, snapshot-like aesthetic formed the basis for Evans’ career, which later extended into unusual framing or cropping used to create the abstract and modernistic atmosphere of many of his early studies of buildings and natural features. In his later, mature work, Evans explored a flatter, two-dimensional look. One of his most famous portraits of two New York City subway passengers in 1941 was cleverly developed in a way that combined the edges of two adjacent negatives from the same film strip into one image to make the people appear to be naturally sitting next to each other. These examples demonstrate some of the courageous ways in which Evans was ready to ignore or flaunt the usual conventions of his medium. The exhibition also includes a few of Evans’ paintings (see the picture below), which are similarly flat and two-dimensional like his photographs in such an extreme way that even the tour guide wryly stated that they would not warrant an exhibition of their own.

Robert Rauschenberg: White Paintings (1951), and, on the right, a portion of Robert Rauschenberg with John Cage: Automobile Tire Print (1953)

Robert Rauschenberg: White Paintings (1951), and, on the right, a portion of Robert Rauschenberg with John Cage: Automobile Tire Print (1953)

Just before Evans embarked on his trip to Europe, Robert Rauschenberg was born in 1925 in Port Arthur, Texas. The similarities in his challenging attitudes toward the conventions of art are made clear in the subtitle of the exhibition, Robert Rauschenberg: Erasing the Rules. With over 150 items, the exhibition aims to highlight Rauschenberg’s efforts to “transform the technical and expressive limits” of the different media that he worked in. Some of the earliest pieces on display are photographs of Rauschenberg’s colleagues, including John Cage and Cy Twombly, as well as full-size exposures made on photosensitive paper with his then-wife Susan Weil.

Robert Rauschenberg:

Robert Rauschenberg:

Mud Muse (1968-1971)These examples reveal the importance of collaboration in Rauschenberg’s work, a trait that is readily apparent in the room devoted to his earliest experimental pieces. They include the clever book This Is the First Half of a Print Designed to Exist in Passing Time (ca. 1949), in which Rauschenberg cut away increasingly large strips from a solid black-ink print block until the image would presumably become all white. A similar theme of disappearance can be seen in the highlight of the room, Rauschenberg’s remarkable Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), which also supplied the title for the exhibition. John Cage, who had been inspired to compose 4:33 (1952) by Rauschenberg’s White Paintings (1951), also drove the car that was used to make Automobile Tire Print (1953) on more than 20 pieces of paper that had been taped together in the manner of a scroll. Its creation has been considered a performance piece. Cage’s partner Merce Cunningham also collaborated regularly with Rauschenberg, and many videos of him and his company’s dancers using Rauschenberg’s sets and/or choreography, sometimes with Rauschenberg himself on stage as well, can be viewed on video screens and in photographs throughout the exhibition.

Much of Rauschenberg’s work demonstrates an interest in technology, as can be seen in the pneumatically-operated Mud Muse (1968-1971), which represents yet another collaborative piece that was created with the assistance of “executives and engineers” from Teledyne and ended up looking like a set piece from some kind of cheap, science fiction B-movie. Similarly, images of astronauts appear in many of the silk screens that Rauschenberg created in the 1960s, such as Retroactive I (1963). On the other hand, much of Rauschenberg’s work also recalls Evans’ primitive images of the American vernacular. The austerity of the infamous Bed (1955), which is simplistically built to hold only one person under a traditional Americana quilt, can be seen as reminiscent of Evans’ famous photographs of impoverished rural areas during the Great Depression. A connection between the two artists can be further discerned from the ubiquity in Rauschenberg’s work of such vernacular elements as cut-outs from popular magazines, logos from the tops of sardine cans, and well-known comic strips that appear in pieces such as the platform for Monogram (1955-1959) or the image of the ‘Court Motel’ featured in Triathlon (2005).

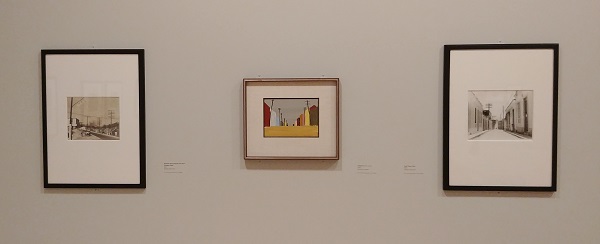

Walker Evans: Roadside View, Alabama Coal Area Company Town (1935), Untitled [Street Scene] (1950s), and Small Town, Cuba (1933)

Walker Evans: Roadside View, Alabama Coal Area Company Town (1935), Untitled [Street Scene] (1950s), and Small Town, Cuba (1933)

In striking contrast to Erasing the Rules and despite being the first comprehensive retrospective of its kind, Walker Evans is arranged thematically instead of chronologically and therefore unfortunately does not give a clear idea of the trajectory of Evans’ career despite laying out its origins at the beginning, as mentioned above, and providing a comprehensive timeline of his life and career at the end on the last wall. Otherwise, the exhibition is presented in two parts. The first part provides an overview of Evans’ career, starting with the Paris snapshots and including some examples from the photographers who inspired him, especially Eugène Atget. It also features Evans’ best-known works, such as the Farm Service Administration photographs taken in Alabama in the late 1930s, and his most famous portrait from that time, Alabama Tenant Farmer Wife (1936), of Allie Mae Burroughs is effectively reinforced by an audio recording of an interview conducted with her in the 1970s.

Most of the exhibition is arranged thematically, especially in the second part. Entire rooms or sections are devoted Evans’ portraits of laborers, a study of wooden churches in New England, random passers-by on a street corner in Chicago or subway riders in New York, posters, shop signs (including examples the original ones that he physically collected), tools, even circus wagons, junkyards, and random, unappealing trash on the street, some in color, all of which further represent the theme of the American vernacular and its landscape that ubiquitously consists mostly of advertising and other commercial artifacts. The images are further complemented by photographs taken by Evans in Cuba or of African artifacts, while other pictures of photography stores and equipment represent a self-directed exploration of his own medium. Ultimately, the exhibition leaves it entirely up to the viewer to piece together the ways in which these varied elements appeared in and historically influenced Evans’ life and career.

Anri Sala: Moth in B-Flat (2015)

Anri Sala: Moth in B-Flat (2015)

After spending the last few years of his life taking Polaroid snapshots of friends and relatives on film that was provided by Kodak for free, Evans passed away in 1975. That same decade, Rauschenberg moved from New York City to Captiva Island, Florida, where his work took on a decidedly more rustic and breezy look, incorporating natural elements such as sand and seashells and using shipping supplies like cardboard boxes, heavy rope, and cloth. Rauschenberg continued developing and working in these and many more new media until passing away in 2008. Just as the last item in the Walker Evans exhibition is Sedat Pakay’s documentary film Walker Evans: His Time, His Presence, His Silence (1969), which features favored music from Evans’ early period and interviews about his life and career, Rauschenberg also worked with sound, as reflected by the taped score made up of different sounds for the ballet Pelican (1963) and the noises produced by several of his kinetic combines and sculptures.

Such works tie in with Soundtracks, the third special exhibition that is currently on display at the SFMOMA. It features a lavish assembly of contemporary, often large-scale, works that feature sound as a medium, such as Céleste Boursier-Mougenot’s clinamen v.2 (2012-ongoing) in which ceramic bowls float in an artificial pool while randomly clinking and clanking into each other in a slow, calming manner. Several of the pieces are presented in darkened galleries, such as Brian Eno’s New Urban Spaces Series #4: “Compact Forest Proposal” (2001), which is constructed of towers of intertwined, yellowish lightbulbs that resemble trees. Ragnar Kjartansson’s The Visitors (2102) is an impressive multi-screen projection of several musicians simultaneously performing an original song in different rooms of an old mansion before gathering on the porch and going down to the front lawn to end the performance a cappella. Soundtracks also extends to a series of Electrical Walks San Francisco (2017) designed by Christina Kubisch in order to “discover the city’s hidden electromagnetic fields through sound” by using special headphones available from the museum (https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/sfmomamedia/media/uploads/files/Soundracks_ExhibitionGuide_FA_Web.pdf).

Exhibition Information:

Soundtracks, July 15, 2017–January 1, 2018 (https://www.sfmoma.org/exhibition/soundtracks/)

Walker Evans, September 30, 2017–February 4, 2018 (https://www.sfmoma.org/exhibition/walker-evans/)

Robert Rauschenberg: Erasing the Rules, November 18, 2017–March 25, 2018 (https://www.sfmoma.org/exhibition/robert-rauschenberg-erasing-rules/)