Maria B. Garda

Video games have a short but complex history. This legacy is becoming more and more relevant even to non-gamers. Everyone, in the modern transmedia world, is exposed to the poetics of the playful medium as it invades other popular aesthetic discourses. It even seems much harder not to be a gamer than to be one. Especially, when you are in possession of a mobile device, such as a tablet or smartphone. But the history of video games was never easier to engage with – thanks to the growing numbers of dedicated museums and other heritage projects [1]. One of the most interesting initiatives in this area is currently under development in Finland.

Suomen Pelimuseo [2] (The Finnish Museum of Games) in Tampere is due to open in 2017 when it will become a part of the Vapriikki museum centre, positioning video games in the context of the art museum. The important preservation efforts undertaken by these institutions will help us understand the aesthetic histories of electronic entertainment. When ultimately all of the original equipment will fail, the memory of Pac-man will be still transmitted to new generations of gamers. But even today young players need to be introduced to the practices and aesthetics of early video games, or as they are called by their older colleagues, “classic games”. What is more, in the times of the unfading la mode retro, when pixel art, chiptunes and obsolete mechanics are selling games on the newest consoles, the notion of historical poetics seems more relevant than ever. It shows us that in art nothing comes from nothing.

WHAT IS HISTORICAL POETICS?

Historical poetics, according to film researcher David Bordwell, is “the effort to understand how artworks assume certain forms within a period or across periods” [3]. It is a study absorbed by the historical circumstances (e.g. institutional, social, technological) that determine the creative process. The focal point of the inquiry explores the “zone of choice” available to the game developer: it investigates the horizon of possibilities available to game designers at any given time. Historical poetics, to paraphrase Bordwell himself, wants to know the game developers’ secrets at a specific place and time – and especially those they don’t know they know.

At the same time, it embraces the neoformalist understanding of aesthetic norms, usually analyzing a body of conventions, such as a genre. The study of genres – especially those already as well established as cRPG (computer Role-Playing Games) or adventure games (story-driven puzzle solving) – can improve our comprehension of past gaming cultures. While these forms of gameplay experience have accompanied gamers for over 30 years, taking a closer look at the different stages of their development can inform us about the nature of video games.

CLASSIC NOW AND THEN

One of the many indications for assuming video games to have a considerably complex past are popular rankings such as the recent The 50 Best RPG On PC [4] published by The Rock, Paper, Shotgun (RPS) blog. The authors claim to have investigated “the entire history” of cRPGs in order to shortlist the “best games”. Even though ‘the best of’ form is not a new idea in video game journalism – or perhaps precisely because it is not new – it is a perfect case study to present the importance of the historical poetics approach. Undoubtedly erudite and entertaining, the ranking is a successful exercise of its sort, but from the point of view of a historian it has some disturbing flaws.

First of all, this kind of approach to history creates canons and master narratives that determine which titles will be remembered and which ones will become obsolete. The dominant master narrative of video games is focused on the North American gaming industry and reception. Interestingly, even though the RPS blog is based in the United Kingdom, it fails to recognize many important European cRPG games, such as Gothic (Piranha Bytes 1997-) and Amber Trilogy (Thalion Software 1992–93).

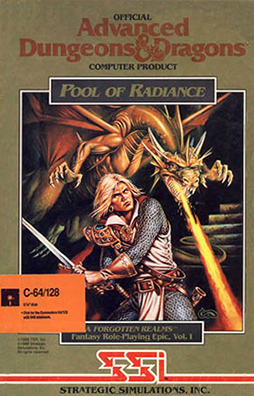

Secondly, comparing the popular titles from the 1980s to the latest premieres, like the Polish dark fantasy best-seller The Witcher 3 (CD Projekt RED 2015), is not very functional. The core of the cRPG genre at the turn of the decades of the 1980s and 1990s was constituted by then famous games such as Pool of Radiance (SSI 1988), and has not much to do with the contemporary cRPG poetics. Not just because of the inevitable technical differences, but above all the game design choices.

Pool of Radiance, Cover Art

Pool of Radiance, Cover Art

Pool of Radiance was praised by journalists of the era as “the best game of the genre ever created” [5] – not surprisingly a title that since 1988 was given to many other productions. Designed for, what would we call from today’s perspective, a “hardcore” audience, Pool of Radiance offers a very different and significantly less diversified gameplay experience compared to contemporary iterations of the genre. The heavily combat oriented progress combined with a steep learning curve limits the freedom of the player. An important factor to The Witcher 3 designers who recognize numerous strategies of gameplay and various types of players; something that was not a part of the gaming culture in 1988. Nevertheless, Pool of Radiance was a very successful adaptation of the Advanced Dungeons and Dragons tabletop role-playing game to the personal computer platform. The game’s engine was reused in the extremely popular Gold Box series. It was arguably the first period in the cRPG genre’s history when it reached a certain stage of coherence and constituted a visible poetics that was not only copied but also developed with artistic success by others. It is not without reason that Matt Barton calls that period the “Golden Age” of the cRPG genre [6].

The “Golden Age” label is, in many respects, similar to the “classic games” term. It incorporates a kind of approach to the video game’s past that Jaakko Suominen identifies as “enthusiast histories” [7]. Enthusiast histories can fetishize selected periods of video game evolution, for example, due to the personal nostalgia of the authors, or present a teleological view of the medium’s history. As Melanie Swalwell points out, “to claim that something is a ‘classic’ is ultimately to make a judgment about its cultural status, value and meaning” [8]. However, the criteria of this judgment are often unclear and it seems like another way to create a master narrative. What is more, one may say that a contemporary title, say The Witcher 3, is an “instant classic”, a statement that is actually suggested in the RPS’s ranking, where the CD Projekt RED’s game is ranked 7th (out of 50).

Regardless of this controversy, Barton and RPS are, to a certain extent, right. Both publications correctly point out the games that constituted the cRPG’s core, however, only in regard to a given period and within a certain local reception history. Note that this type of periodization has certain similarities to the sequential narrative of computer architecture (8 bit, 16 bit and so on) but does not encompass the teleological aspect of narratives of technological progress. Earlier temporal variations of the genre aren’t any worse than the newest.

To sum up, it is more functional – at least as far as historical poetics is concerned – to compare the Betrayal at Krondor (Dynamix 1993) to the Pool of Radiance than to The Witcher 3. Game designers in 1993 had different possibilities, motivations and points of reference then than they do today. Therefore, we should compare The Witcher 3 to the titles from its own period, such as Skyrim (Bethesda 2011). In fact, it was done many times by the developers themselves [9], when they emphasized the unprecedented scale of the game world, arguably larger then the one in Skyrim. Another important issue is to acknowledge the local context of a game. For example, the first iteration in the Witcher series, The Witcher (CD Projekt RED 2007), was a less global market oriented product than The Witcher 3 and should thus be confronted with the regionally significant titles such as the German Gothic (Piranha Bytes, 2001) published in Poland in 2002.

Gothic, Cover Art

Gothic, Cover Art

Finally, I don’t want to say that analyzing the whole body of the cRPG genre is not useful, but while “we identify the genre to interpret the exemplar” [10] I find it more adequate to use a prototype situated within the closest historical context than in a very different period of gaming culture – with one exception.

CLASSIC AND CLASSIC-LIKE

As I mentioned before, there is a modern wave of games inspired by the retroaesthetics of the so-called “classic games” of the 1980s and 1990s. A good example of this trend is a set of games that I label “neo-rogue”. The design of these contemporary titles is heavily influenced by the roguelike subgenre of cRPG.

Rogue Unix, Screen Shot

Rogue Unix, Screen Shot

Named after the famous Rogue (Toy, Wichman and Arnold, 1980), roguelikes are best known for text based interface, randomly generated content and permanent death. The subgenre flourished in the 1980s, but in the next decade it became somewhat obsolete. However, recently it experiences a renaissance. Productions such as FTL: Faster Than Light (Subset Games 2012), a Kickstarter-funded spaceship simulator, use the dominant aesthetic effects of the roguelike form (predominantly permanent death) and consciously redefine them in the new game design paradigm of indie games. They are no longer “classic” roguelikes but they are in the constant dialogue with the “classic” core of the genre.

As we can see, a historical poetics approach to those games influenced by retroaesthetics is a special case, because it requires a comparative study and demands a juxtaposition with past exemplars of the genre.

MOVING ON FROM THE CLASSIC

A historical poetics of video games consists of a wide spectrum of aesthetic effects. Many video games are influenced by other media, yet they are no less products of the medium’s own evolution. The temporal distance that separates contemporary game development from the formative – or so-called “classic” – periods of the now established genres allows for reflection on past styles. Video games should be interpreted within the context of a given genre’s historical poetics. It is important to recognize the empirical circumstances of the period when the game was created and the body of games and conventions that were points of reference for the developers. When exploring these juxtapositions, it is vitally important to acknowledge also the local context of the genre’s reception, as the ranking of “the best RPGs” can significantly differ from one region to another.

Maria B. Garda is an Assistant Lecturer in the School of Media and Audiovisual Culture at the University of ?ód? and Investigator on the Polish National Science Center project “New Media PRL”. She is a co-editor of the Replay. Polish Journal of Game Studies and co-chair of the annual Computer Games Culture conference. She is interested in the history of video game cultures, the demoscene and digital media preservation.

References:

[1] Just to mention a few: Computerspielemuseum in Berlin or the Play it Again Project in Australia.

[2] More information at Mesenaatti.me

[3] David Bordwell, Poetics of cinema (New York, London: Routledge, 2008), 13.

[4] The 50 Best RPG on PC

[5] Tony Dillon, “Pool of Radiance”, Commodore user 1988, 34-35.

[6] Matt Burton, Dungeons and desktops: the history of computer role-playing games. Wellesley, Mass.: A K Peters, 2008, viii.

[7] Jaakko Suominen, How to present the history of digital games (paper presented in Critical evaluation of game studies seminar in Tampere, 2014).

[8] Melanie Swalwell, “Classic Games”, in Debugging Game History: A critical lexicon. Edited by Henry Lowood, and Raiford Guins (Cambridge: MIT Press, forthcoming).

[9] Erik Kain, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt’ Bigger Than Skyrim, 30 Times the Size of a Whitcher 2, Forbes

[10] Alastair Fowler, Kinds of literature. An introduction to the theory of genres and modes (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press), 38.

[11] Maria B. Garda, “Neo-rogue and essence of roguelikeness”, Homo Ludens 4 (2013): 59-72.

[12] Fowler, Kinds of literature, 134.