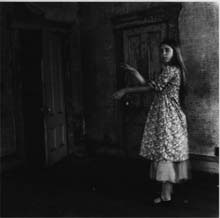

Francesca Woodman

Francesca Woodman

The recent Donna: Avantguardia Feminista Negli Anni 70 exhibition presented 17 radical women artists from the 70’s. While some of them like Martha Rosler, Cindy Sherman, Hannah Wilke, Ana Mendieta and Valie Export are well known by now, some participants of the exhibition are very little known to a larger public, for instance Ketty la Rocca, Nil Yalter and Birgit Jürgensen. These artists did not get much attention during their lifetime.

I did not have the opportunity to see the exhibition in Rome, but as the curator Gabriele Schor kindly sent me the publication of the exhibition, I would like to comment shortly the topic of avant-garde.

The most important thing in the exhibition was that women’s radical art is presented in the context of avant-garde studies. Gabriele Schor writes that “the women’s movement in art can be considered as an avant-garde because its members are united by a desire to change the existing social forms of the art world” in reference to Lawrence Alloway’s text “Women’s Art in the 70” (1976).

This is correct: women artists did not only want to transform the social forms of the art world, they also criticized and aimed to change the social norms and beliefs concerning woman’s place in society. To obtain this they developed new experimental practices by using photography, video and performance. In the 70’s art these practices were not only unusual, they had a shock-effect that can be compared to the historical avant-garde like Surrealism or Dadaism.

Gabriele Schor points out that in the 70’s it was still painting, and especially American style abstract expressionism that dominated the art institution. In order to be valued as an artist, one had to follow “macho, working class ethics” i.e. to be a male painter. Jackson Pollock was the typical ideal of the contemporary art. His wife, Lee Krasner, who is recognized now, was not regarded as an artist in the 60’s and 70’s at all.

Women artists presented in the Donna 70 rejected painting as a medium and chose photography instead. It is interesting that artists like Cindy Sherman, Birgit Jürgenssen and Francesca Woodman did this almost at the same time, as if on the basis of a common agreement. Cindy Sherman who had a traditional training in painting has said that she couldn’t express herself with this medium. Photography that was historically unfettered offered her a more liberated and spontaneous medium for expression.

An overview from the Donna 70 exhibition

An overview from the Donna 70 exhibition

Women artists replaced the traditional painterly space studied by modernist male artists with a new experimental space opened up in photography. Their work often carried a performative mode. Preferring the autonomy of their studio they established a dialogue between their work and themselves, Gabriele Shor writes. In spite of their differences they all performed for the camera without an audience being present, Shor notes. In my mind Shor’s detailed analysis of the avant-garde experimental practices of women’s art in the 70’s is an important contribution to the discourse of feminist art and avant-garde studies as well.

In brief, one could say that the radical female artists of the 70’s changed the focus of art from the modernist questions of representation and aesthetics to existential, ethical and political questions. Women’s works did not attract attention with the big size or aesthetic properties like the paintings of the contemporary male artists, but due to their intelligent and controversial content and highly experimental practices. What was at stake was a new idea, a new concept. The questions of identity, not ‘Who am I’ but ‘Where am I’ replaced the traditional aesthetic questions. This is a typical avant-garde strategy.

***

Now that nearly 40 years have passed since the introduction of these works one would like to ask the effects of the avant-garde of the 70’s. The first impression is that the experimental practices of women’s art have been largely adopted in contemporary art. Numerous present artists, both men and women do portraiture and even self-portraiture using photography and video as a means. Nowadays this kind of art does not, however, have the similar avant-garde relevance as the art of 70’s.

If one looks at the works of the Finnish photography school called the Helsinki School for instance, one can easily find that many of its members share the visual characteristics of the radical women’s art of the 70’s. Even the artists’ statements resemble the questioning of the 70’s.

Susanna Majuri writes: “I suggest: we can be multiple. Touch your environment, and it

will show itself as fantastic. People are unpredictable. They are male and female at the same time. Eyes whisper sparks.”

Anni Leppälä

Anni Leppälä

Anni Leppälä, who has been chosen as the young artist of the year 2010 in Finland uses similar visual language as the women avant-garde of the 70’s. She establishes complex and mysterious choreographs and performances in her photographs, where persons masquerade and hide themselves playing multiple roles. Her visual language may resemble that of the early feminist avant-garde, but there is no radical questioning of one’s identity or roles in society, no political agenda at all.

Also the male photographers of the Helsinki school have adopted the similar style of expression. It is not difficult to observe that the contemporary artists who use photography and performatives do not reach for any political or critical meaning whatsoever. What used to be alternative and radical practices in the 70’s has been neutralized into simple style of expression.

Performing to the camera has become a commonplace without the complex questions of self or one’s place in the world. For instance Elina Brotherus poses happily to the camera in beautiful and painterly landscapes, which in her mind only reflect the tradition of landscape painting. In her art every element of the radicalism of her predecessors has been eliminated and the idea of narcissism has, perhaps unanimously, slipped in.

It is difficult to say in what way the ideas and practices of the experimental art of 70’s came to contemporary photography. Probably the influences are not intentional. Anyway, I remember that the radical feminist theory was intensively studied in 90’s in the Helsinki University of Industrial Arts (UIAH) where the present Helsinki School originated.

Unlike the Helsinki school the feminist art of the 70’s still appears provocative and politically compelling. So it is still avant-garde. One has only to consider the way the female body is presented in feminist art. In the 70’s a woman’s body was a serious and sore matter. It was also a personal matter. As a rule the body appeared as abused and suffering, desired and despised at the same time. In Hannah Wilke’s works the borderline between the glorification and disdain of the body is very delicate.

Anni Leppälä

Anni Leppälä

While in the avant-garde of the 70’s the (female) body and its sexuality carried a strong political message due to the way it was presented, in present photography of Helsinki school for instance this is not so. The bodies do not belong to anyone, as the persons depicted are anonymous. Maybe this is the reason why the contemporary photography – in spite of its other merits – has lost its avant-garde character?

Link:

Helsinki school